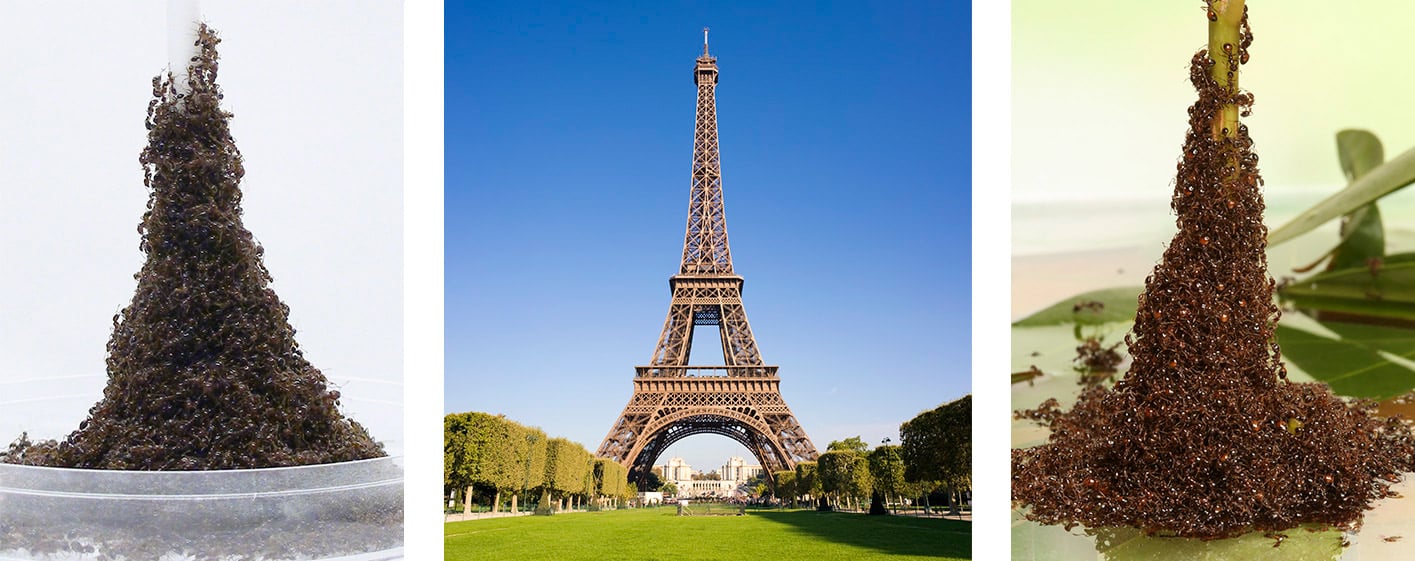

Fire ants use their bodies to build tower-like structures —all without a plan, a leader, or coordinated effort, new research suggests.

Each ant, researchers say, wanders around aimlessly, adhering to a certain set of rules, until it unknowingly participates in the construction of a tower several inches tall.

“If you watched ants for 30 seconds, you could have no idea that something miraculous would be created in 20 minutes,” says coauthor David Hu, a professor in the Georgia Institute of Technology’s George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering. “With no planning, and using trial-and-error, they create a bell-shaped structure that helps them survive.”

The tower study is a follow-up to the group’s 2014 ant raft research, which examined how the insects link their bodies in order to build waterproof structures that stay afloat for months. The ants march along until they come to an open space—the edge of the raft—then settle in to become a building block of the raft.

They do the same thing for the towers, searching for an empty spot like a car in a crowded parking lot. Once an individual ant finds one, typically at the top of the tower, she stops and braces for more ants to climb on top and go vertical.

They build these towers when they run into a tall obstruction while looking for food or escaping to new areas.

But vertical is a relative term. The ants don’t position themselves straight up and down like a skyscraper. Instead, the tower gets wider as it grows taller, gradually becoming the same shape as Paris’ iconic landmark. The weight of the tower is supported by a wider cross-section at its base, which allows the ants to better distribute their weight.

“The tower is constantly rebuilding and replacing its surface.”

“We found that ants can withstand 750 times their body weight without injury, but they seem to be most comfortable supporting three ants on their backs,” says Craig Tovey, a coauthor of the study and professor in the Stewart School of Industrial & Systems Engineering. “Any more than three and they’ll simply give up, break their holds, and walk away.”

Even though the ants evenly distribute their weight as a group, the tower is in constant motion. The column sinks as the insects work, as if the bottom is being melted like butter. The ants slide down, then exit out of tunnels buried in the base. The tower’s movement is similar to a slow-motion chocolate fountain in reverse.

The sinking towers were discovered by accident. The researchers planned to record ants building for two hours, but the camera rolled for three.

“We didn’t expect to see anything interesting in that extra hour, so we sped up the video to 10 times real speed,” says Tovey. “We were amazed at how different the ant movements appeared.”

Ants wear smells like a uniform

In real time, they saw ants busily moving on the surface of a tower of apparently stationary ants. At high speed, however, the surface ant movements appeared as a blur and the entire tower slipped downward.

“The tower sinking was too slow to see at real speed,” says Tovey.

The sinking was confirmed by X-ray videography. The researchers fed some of the ants radioactive food, then threw the colony in an X-ray machine across campus in Dan Goldman’s physics lab. Cameras again recorded the critters building a tower. Using time-lapse photography, they watched the radioactive insects walk up the sides, gradually sink to the tower’s depths, leave the pile, then continually repeat the process for hours.

“Ant towers are like human skin,” says Hu, who is also a faculty member in the School of Biological Sciences. “The tower is constantly rebuilding and replacing its surface.”

The findings could have implications for modular robots, which currently aren’t very effective at building tall towers.

Tovey, who is also a biologist, has a different reason for studying ant behavior.

Teeming ants act like both a liquid and a solid

“Ninety-nine percent of all the species that have ever lived on Earth are extinct,” Tovey says. “The rest of us have developed very effective techniques to survive. Why wouldn’t we study these processes? Engineers and scientists don’t always know what our findings will lead to, but bioinspired design can be a powerful tool to make our world more efficient.”

The paper appears in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Source: Georgia Institute of Technology