Instability hidden within Antarctic ice is likely to accelerate its flow into the ocean and push sea level up at a more rapid pace than previously expected, according to a new study.

Images of vanishing Arctic ice and mountain glaciers are jarring, but their potential contributions to sea level rise are no match for Antarctica’s, even if receding southern ice is less eye-catching.

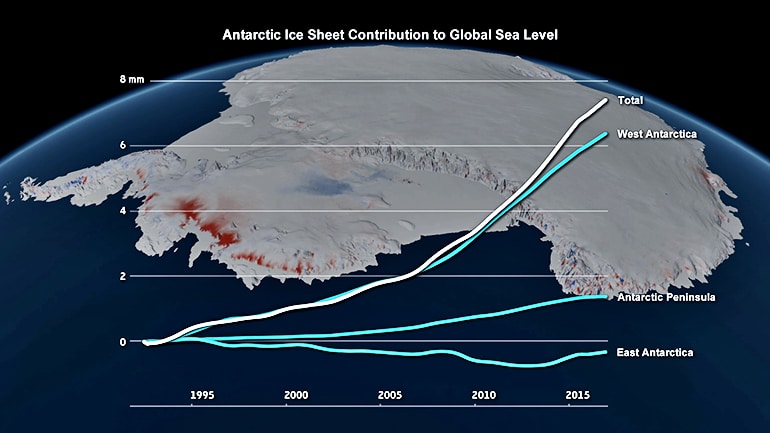

In the last six years, five closely observed Antarctic glaciers have doubled their rate of ice loss, according to the National Science Foundation. At least one, Thwaites Glacier, which researchers modeled for the new study, may be in danger of succumbing to this instability, a volatile process that pushes ice into the ocean fast.

Antarctica’s uncertain future

How much ice the glacier will shed in coming 50 to 800 years can’t exactly be projected due to unpredictable fluctuations in climate and the need for more data. But researchers have factored the instability into 500 ice flow simulations for Thwaites with refined calculations.

The scenarios diverged strongly from each other but together pointed to the eventual triggering of the instability. Even if global warming were to later stop, the instability would keep pushing ice out to sea at an enormously accelerated rate over the coming centuries.

And this is if ice melt due to warming oceans doesn’t get worse than it is today. The study went with present-day ice melt rates because the researchers were interested in the instability factor in itself.

“If you trigger this instability, you don’t need to continue to force the ice sheet by cranking up temperatures. It will keep going by itself, and that’s the worry,” says Alex Robel, an assistant professor in the Georgia Institute of Technology’s School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences who led the study. “Climate variations will still be important after that tipping point because they will determine how fast the ice will move.”

“After reaching the tipping point, Thwaites Glacier could lose all of its ice in a period of 150 years. That would make for a sea level rise of about half a meter (1.64 feet),” says NASA Jet Propulsion Lab scientist Helene Seroussi, who collaborated on the study. For comparison, current sea level is 20 cm (nearly 8 inches) above pre-global warming levels and is blamed for increased coastal flooding.

The study also shows that the instability makes forecasting more uncertain, leading to the broad spread of scenarios. This is particularly relevant to the challenge of engineering against flood dangers.

“You want to engineer critical infrastructure to be resistant against the upper bound of potential sea level scenarios a hundred years from now,” Robel says. “It can mean building your water treatment plants and nuclear reactors for the absolute worst-case scenario, which could be two or three feet of sea level rise from Thwaites Glacier alone, so it’s a huge difference.”

Why is Antarctic ice the big driver of sea level rise?

Arctic sea ice is already floating in water. You may know that 90 percent of an iceberg’s mass is underwater and that when its ice melts, the volume shrinks, resulting in no change in sea level.

But when ice masses long supported by land, like mountain glaciers, melt, the water that ends up in the ocean adds to sea level. Antarctica holds the most land-supported ice, even if the bulk of that land is seabed holding up just part of the ice’s mass, while water holds up part of it. Also, Antarctica is an ice leviathan.

“There’s almost eight times as much ice in the Antarctic ice sheet as there is in the Greenland ice sheet and 50 times as much as in all the mountain glaciers in the world,” Robel says.

Icy ‘instability’

The line between where the ice sheet rests on the seafloor and where it extends over water is called the grounding line. In spots where the bedrock underneath the ice behind the grounding line slopes down, deepening as it moves inland, the instability can kick in.

On deeper beds, ice moves faster because water is giving it a little more lift. Also, warmer ocean water hollows out the bottom of the ice, adding a little more water to the ocean. More importantly, the ice above the hollow loses land contact and flows faster out to sea.

“Once ice is past the grounding line and just over water, it’s contributing to sea level because buoyancy is holding it up more than it was,” Robel says. “Ice flows out into the floating ice shelf and melts or breaks off as icebergs.”

“The process becomes self-perpetuating,” Seroussi says, describing why it is called “instability.”

Borrowing from physics

The researchers borrowed math from statistical physics that calculate what random variables do to predictability in a physical system, like ice flow, when outside forces, like temperature changes, act upon them. They applied the math to simulations of possible future fates of marine glaciers like Thwaite Glacier.

They made an added surprising discovery. Normally, when climate conditions fluctuate strongly, Antarctic ice evens out the effects. Ice flow may increase but gradually, not wildly, but the instability produced the opposite effect in the simulations.

“The system didn’t damp out the fluctuations, it actually amplified them. It increased the chances of rapid ice loss,” Robel says.

How rapid is ‘rapid’?

The study’s time scale was centuries, as is common for sea level studies. In the simulations, Thwaites Glacier colossal ice loss kicked in after 600 years, but it could come sooner.

“It could happen in the next 200 to 600 years. It depends on the bedrock topography under the ice, and we don’t know it in great detail yet,” Seroussi says.

So far, Antarctica and Greenland have lost a small fraction of their ice, but already, shoreline infrastructures face challenges from increased tidal flooding and storm surges. Scientists expect sea level to rise by up to two feet by the end of this century.

For about 2,000 years until the late 1800s, sea level held steady, then it began climbing, according to the Smithsonian Institution. The annual rate of sea level rise has roughly doubled since 1990.

Gerard Roe from the University of Washington is a coauthor of the study, which appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The National Science Foundation and NASA funded the research. Any findings, conclusions or recommendations are those of the authors and not necessarily of the funding agencies.

Source: Georgia Tech