Scientists have deduced that the Andromeda galaxy, our closest large galactic neighbor, shredded and cannibalized a massive galaxy two billion years ago.

Even though it was mostly shredded, this massive galaxy left behind a rich trail of evidence: an almost invisible halo of stars larger than the Andromeda galaxy itself, an elusive stream of stars, and a separate enigmatic compact galaxy, M32. Discovering and studying this decimated galaxy will help astronomers understand how disk galaxies like the Milky Way evolve and survive large mergers.

This disrupted galaxy, named M32p, was the third-largest member of the Local Group of galaxies, after the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies. Using computer models, Richard D’Souza and Eric Bell of the University of Michigan’s astronomy department were able to piece together this evidence, revealing this long-lost sibling of the Milky Way. Their findings appear in Nature Astronomy.

‘Eureka!’

Scientists have long known that this nearly invisible large halo of stars surrounding galaxies contains the remnants of smaller cannibalized galaxies. A galaxy like Andromeda was expected to have consumed hundreds of its smaller companions. Researchers thought this would make it difficult to learn about any single one of them.

Using new computer simulations, the scientists were able to understand that even though Andromeda consumed many companion galaxies, most of the stars in the Andromeda’s outer faint halo came from shredding a single large galaxy.

“It was a ‘eureka’ moment. We realized we could use this information of Andromeda’s outer stellar halo to infer the properties of the largest of these shredded galaxies,” says lead author D’Souza, a postdoctoral researcher.

“Astronomers have been studying the Local Group—the Milky Way, Andromeda, and their companions—for so long. It was shocking to realize that the Milky Way had a large sibling, and we never knew about it,” says coauthor Bell, professor of astronomy.

Meet M32p

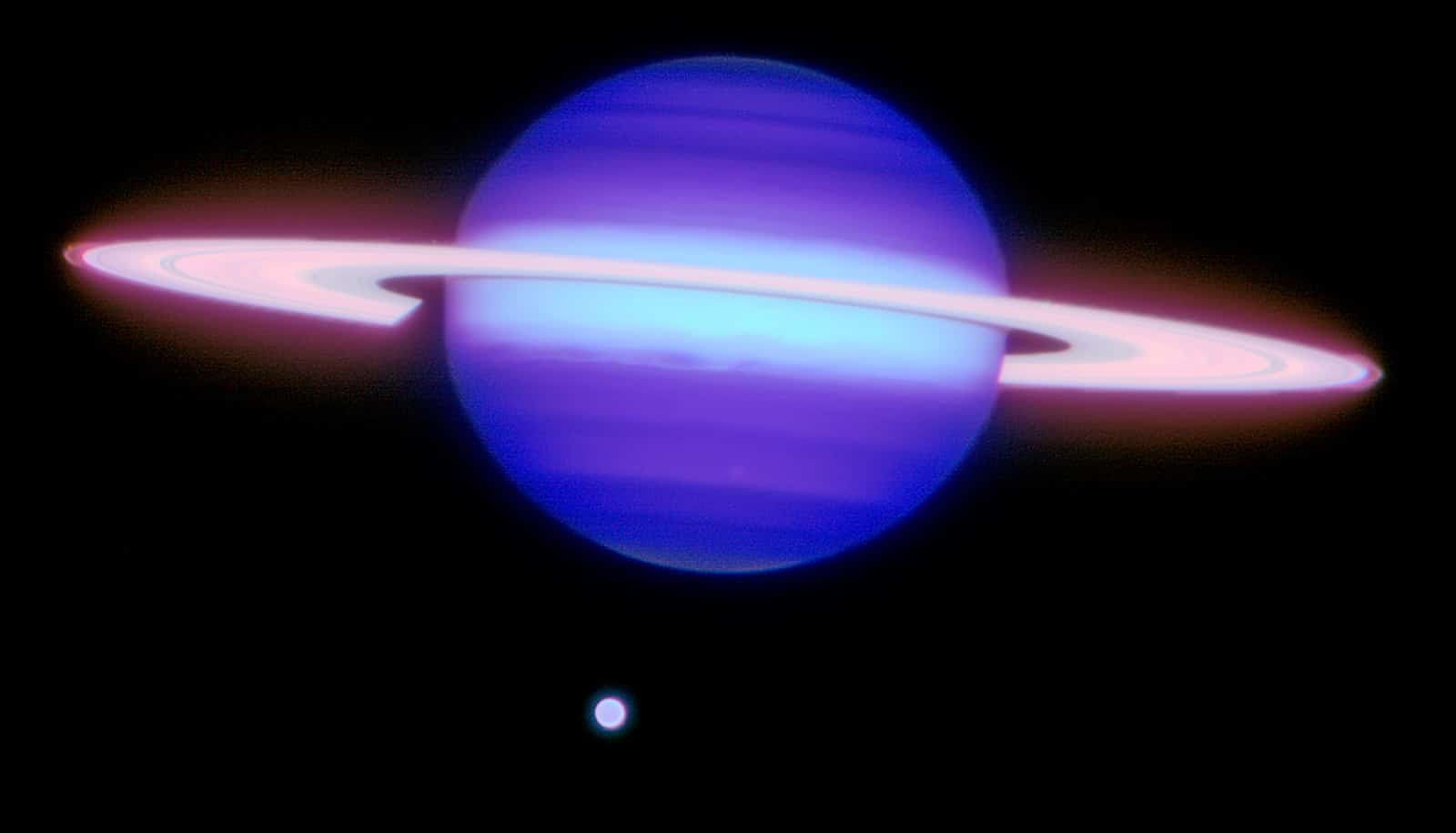

This galaxy, called M32p, which the Andromeda galaxy shredded, was at least 20 times larger than any galaxy which merged with the Milky Way over the course of its lifetime. M32p would have been massive, making it the third largest galaxy in the Local Group after the Andromeda and the Milky Way galaxies.

“M32 is a weirdo.”

This work might also solve a long-standing mystery: the formation of Andromeda’s enigmatic M32 satellite galaxy, the scientists say. They suggest that the compact and dense M32 is the surviving center of the Milky Way’s long-lost sibling, like the indestructible pit of a plum.

“M32 is a weirdo,” Bell says. “While it looks like a compact example of an old, elliptical galaxy, it actually has lots of young stars. It’s one of the most compact galaxies in the universe. There isn’t another galaxy like it.”

The Milky Way ate 11 other galaxies

Their study may alter the traditional understanding of how galaxies evolve, the researchers say. They realized that the Andromeda’s disk survived an impact with a massive galaxy, which would question the common wisdom that such large interactions would destroy disks and form an elliptical galaxy.

The timing of the merger may also explain the thickening of the disk of the Andromeda galaxy as well as a burst of star formation two billion years ago, a finding that French researchers reached independently earlier this year.

How much does our galaxy weigh?

“The Andromeda Galaxy, with a spectacular burst of star formation, would have looked so different 2 billion years ago,” Bell says. “When I was at graduate school, I was told that understanding how the Andromeda Galaxy and its satellite galaxy M32 formed would go a long way towards unraveling the mysteries of galaxy formation.”

The researchers say they could use the method in this study on other galaxies, permitting measurement of their most massive galaxy merger. With this knowledge, scientists can better untangle the complicated web of cause and effect that drives galaxy growth and learn about what mergers do to galaxies.

Source: University of Michigan