Ancient rainfall records stretching 550,000 years into the past may upend scientists’ understanding of what controls the Asian summer monsoon and other aspects of the Earth’s long-term climate, according to a new study.

Milutin Milankovitch developed the standard explanation of the Earth’s regular shifts from ice ages to warm periods in the 1920s. He suggested the oscillations of the planet’s orbit over tens of thousands of years control the climate by varying the amount of heat from the sun falling above the Arctic Circle in the summer.

“Here’s where we turn Milankovitch on its head,” says first author J. Warren Beck, a research scientist in physics and in geosciences at the University of Arizona. “We suggest that, through the monsoons, low-latitude climate may have as much effect on high-latitude climate as the reverse.”

When it rains…

During the northern summer, the subtropics and tropics north of the equator warm and the tropics and subtropics south of the equator cool.

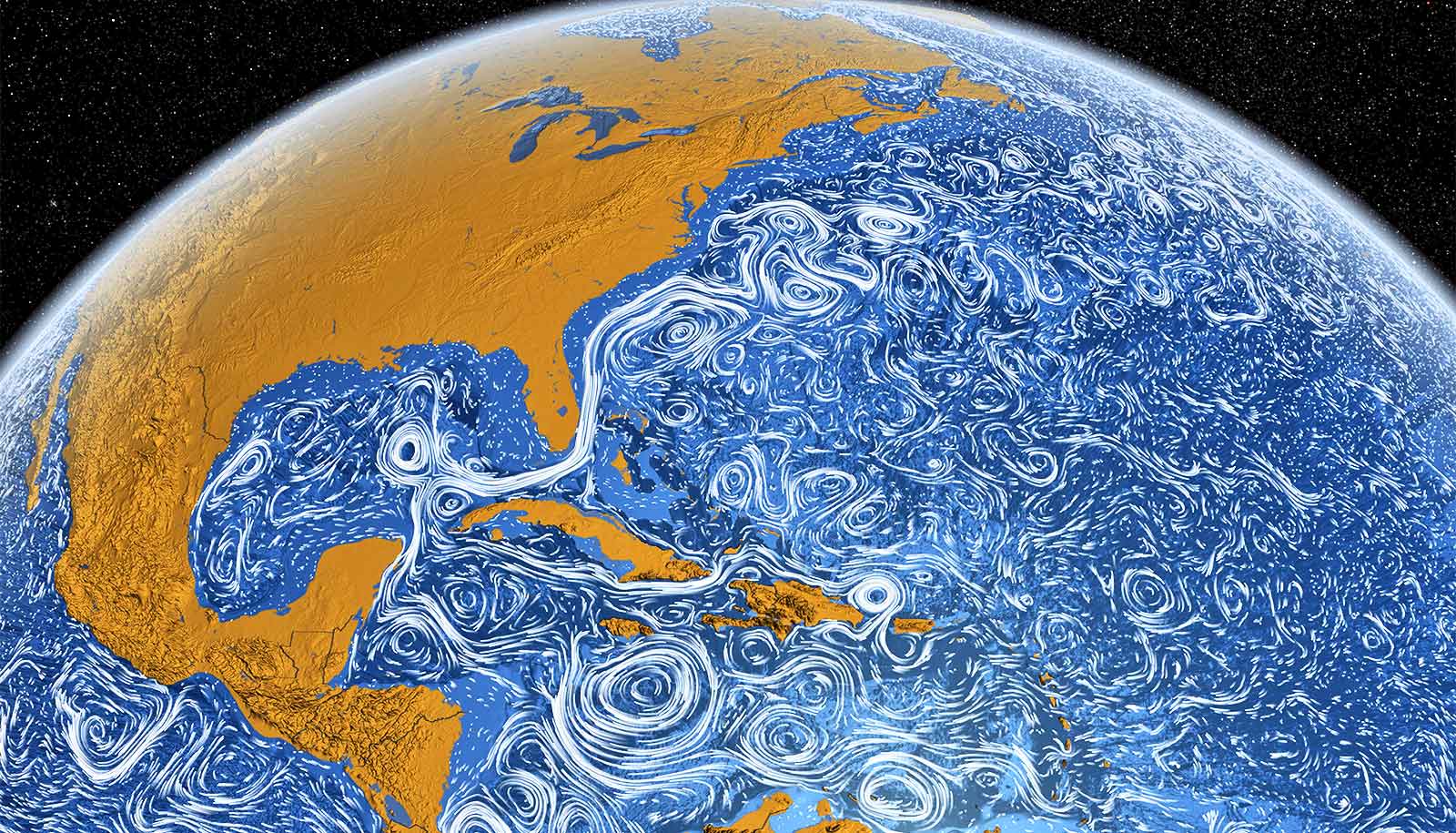

Modern observations show the difference in heat propels atmospheric changes that drive the intensity of the monsoon. Beck says the monsoon can affect wind and ocean currents as far away as the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans.

The Asian monsoon season is the biggest annual rainfall system on Earth and brings rainfall to about half the world’s population. The monsoon season occurs approximately April to September.

Beck and his colleagues found that over tens of thousands of years the changes in the intensity of the Asian summer monsoon corresponded to the waxing and waning of the polar ice caps.

The researchers suggest those long-term changes in the monsoon drove global changes in wind and ocean currents in ways that affected whether the polar ice caps grew or shrank.

Beck says this new explanation of the Earth’s past climate cycles will help climate modelers figure out more about the world’s current and future climate.

The new explanation of what drives the Earth’s climate system stems from a decade-long effort by Beck and his colleagues to develop a new record of rainfall in Asia reaching far back into the past.

Scientists have been trying to develop a quantitative proxy for ancient precipitation for more than 30 years, he says.

By analyzing thousands of years of dust from north-central China for an element called beryllium-10, Beck and his colleagues developed the first quantitative record of the region’s monsoon rainfall for the past 550,000 years.

Digging in the dirt

The team studied the deposits of fine soil called loess that blow year after year from central Asian deserts into north-central China. The layer-cake-like deposits, hundreds of feet thick, are a natural archive extending back millions of years.

The researchers cut stepwise into the side of a hill of loess to expose a 60-yard (55-meter) span of loess representing 550,000 years. The researchers collected a loess sample every two inches (five centimeters). Two inches represents about 500 years.

Cave holds clues to stormy weather 8,200 years ago

Scientists can use the amount of beryllium-10 in soil as a proxy for precipitation, because when it rains the element washes out of the atmosphere on dust particles. Because more rain means more beryllium-10 deposited on the soil, the amount of beryllium-10 deposited at a particular time reflects the intensity of the rainfall.

To put together the ancient rainfall history of the area, team members analyzed the samples for beryllium-10 at the University of Arizona’s Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory and for magnetic susceptibility at the Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute of Earth Environment in Xi’an.

Other investigators used the natural archive of oxygen isotopes within stalagmites from several Chinese caves to reconstruct the region’s past climate. Those records only partially agree with the rainfall-based records of ancient climate developed by Beck and his colleagues.

Beck and his colleagues suggest their new explanation of the forces driving the Earth’s long-term climate cycles reconciles the climate record from Chinese stalagmites and modern observations of the monsoon with the new ancient rainfall record from Chinese loess.

China sees 50% drop in severe weather since 1960

The research appears in the journal Science.

Additional coauthors are from the Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences in Xi’an and Jiaotong University in Xi’an.

The US National Science Foundation, the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, the National Science Foundations of China, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences funded the research.

Source: University of Arizona