Increased glucose, transformed into energy, could give people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, improved mobility and a longer life, according to new research.

Physicians have long known that people with ALS experience changes in their metabolism that often lead to rapid weight loss in a process called hypermetabolism. According to the study’s lead author Ernesto Manzo, a postdoctoral researcher in the molecular and cellular biology department at the University of Arizona, hypermetabolism can be a relentless cycle.

People with ALS use more energy while resting than those without the disease, while simultaneously they often struggle to effectively make use of glucose, the precise ingredient a body needs to make more energy. Experts have not known exactly what happens in a patient’s cells to cause this dysfunction or how to alleviate it.

“This project was a way to parse out those details,” says Manzo, who described the results, which appear in eLife, as “truly shocking.”

Slowing ALS down

The researchers found that when they gave ALS-affected neurons more glucose, they turn that power source into energy. With that energy, they’re able to survive longer and function better. Increasing glucose delivery to the cells, then, may be one way to meet the abnormally high energy demands of ALS patients.

“These neurons were finding some relief by breaking down glucose and getting more cellular energy,” Manzo says.

ALS is almost always a progressive disease, eventually taking away patients’ ability to walk, speak, and even breathe. The average life expectancy of an ALS patient from the time of diagnosis is two to five years.

“ALS is a devastating disease,” says senior author Daniela Zarnescu, a professor of molecular and cellular biology. “It renders people from functioning one day to rapidly and visibly deteriorating.”

Previous studies on metabolism in ALS patients have focused primarily on what happens at the whole-body level, not the cellular level, Zarnescu explains.

“The fact that we uncovered a compensatory mechanism surprised me,” Zarnescu says. “These desperate, degenerating neurons showed incredible resilience. It is an example of how amazing cells are at dealing with stress.”

Learning from fruit flies

The novelty of the findings partially lies in the fact that metabolism in ALS patients has remained poorly understood, Zarnescu says.

“It’s difficult to study, in part because of limited accessibility to the nervous system,” she says.

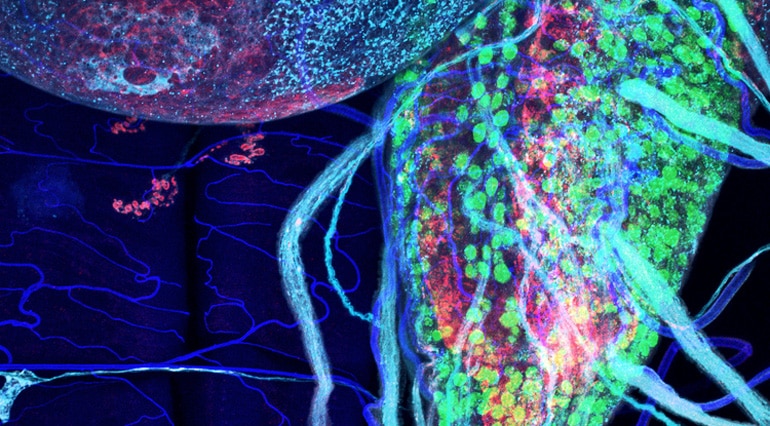

Because scientists can’t scrape away neurons from the brain without causing irreparable damage to a patient, the researchers used fruit flies as a model.

“Fruit flies can teach us a lot about human diseases,” Manzo says.

In the lab, he and Zarnescu used high-powered microscopes to observe the motor neurons of fruit flies in their larval state, paying close attention to what happened as they provided more glucose.

They found that when they increased the amount of glucose, the motor neurons lived longer and moved more efficiently. When the researchers took glucose away from the neurons, the fruit fly larva moved more slowly.

Their findings were consistent with a pilot clinical trial, which found a high carbohydrate diet was one possible intervention for ALS patients with gross metabolic dysfunction.

“Our data essentially provide an explanation for why that approach might work,” Zarnescu says. “My goal is to convince clinicians to perform a larger clinical trial to test this idea.”

Additional coauthors are from the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix and Université de Montpellier in France. The National Institutes of Health partially funded the research.

Source: University of Arizona