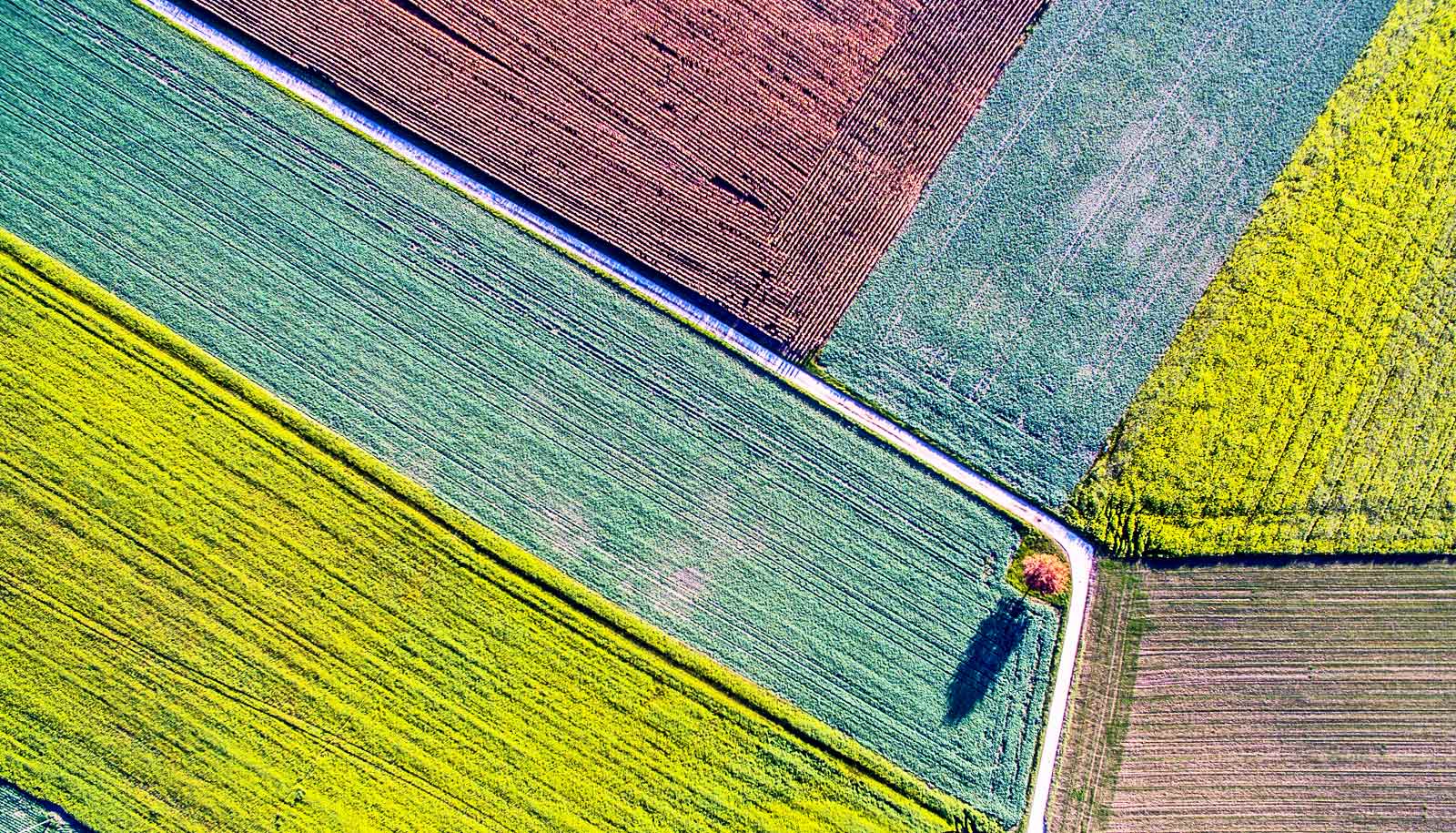

The spatial arrangement of crop fields, forests, and grasslands does a lot to determine how many critters like spiders and lady beetles show up in a field to eat pests.

These tiny invertebrate bodyguards protect crops from pests, making it easier for farms to grow our food.

A new review article in Trends in Ecology and Evolution summarizes recent research into ways landscape configuration affects natural enemies and pest suppression.

“One of the take-homes from our review is that natural enemies can be more abundant when agricultural landscapes are made up of smaller farm fields,” says coauthor Nate Haan, postdoctoral researcher in the Michigan State University entomology department.

“Some natural enemies need resources found in other habitats or in crop field edges. We think when habitat patches are small, they are more likely to find their way back and forth between these habitats and crop fields, or from one crop field into another.”

Haan emphasizes that the exact effects of landscape configuration depend on the natural history of the critter in question.

“A predator that finds everything it needs to survive within a single crop field might not need natural habitats outside that crop field, but there are lots of other insects that need to find nectar or shelter in other places,” Haan says. “For these insects, the spatial arrangement of crop fields and those other habitats can become very important.”

This research will help scientists predict how future changes to farming landscapes will affect insect diversity and pest suppression, a service that is estimated to save farmers billions of dollars every year.

One expected change to landscapes in the Midwest will occur as farmers begin to grow more bioenergy crops. This is a key interest of the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center, or GLBRC, which funded the study.

Farmers are likely to grow more crops that can become substitutes for petroleum; these crops could be traditional crops like corn, but switchgrass, poplar trees, and native prairie are promising alternatives. Depending the crop and its location, future landscapes will contain new habitats and will likely be in new spatial arrangements.

The next steps for this research include learning more about whether life history traits of beneficial arthropods predict how they will respond to landscape change. Insects have different food requirements and strategies for moving around the landscape, Haan and colleagues are excited to learn how these differences can be used to predict how the insects will respond to future landscape changes.

Source: Joy Landis for Michigan State University