A team of scientists has uncovered a neurological synergy that occurs in visual adaptation, a phenomenon in which prolonged exposure to a stimulus alters perception.

Well-known examples include the “motion aftereffect” and “facial expression aftereffect.” In the former, staring at a moving stimulus—for example, a waterfall—and then shifting gaze to a steady object—such as a nearby rock—causes an illusion in which the “steady” object (the rock) appears to move in the opposite direction.

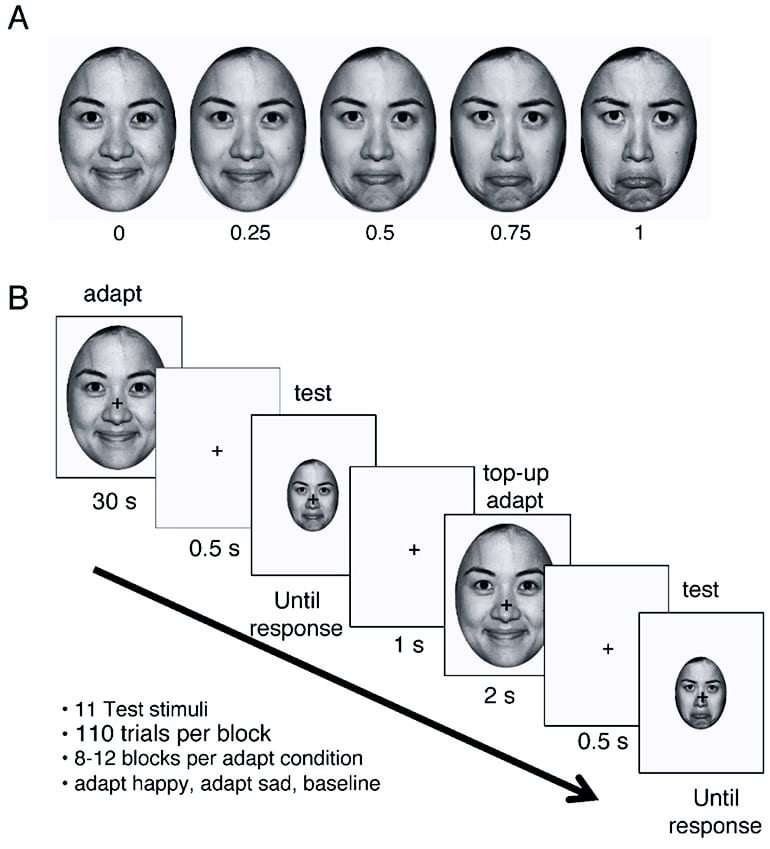

In the facial expression adaptation, after viewing a face with a beaming smile, faces with a neutral expression appear sad, while viewing a sad face causes a neutral face to appear happy.

The new study, which appears in the Journal of Vision, challenges a common assumption that adaptation aftereffects are purely sensory. By quantifying the relationship between altered sensory responses and how we act on it, the scientists determined that adaptation could change how sensory neurons respond to stimuli as well as how we decide based on these altered responses.

“We come across optical illusions in our daily lives, but how our behavior is shaped by them is not well understood,” explains Roozbeh Kiani, an assistant professor in New York University’s Center for Neural Science and the study’s senior author. “Our findings show two separate processes function in a synergistic fashion.”

Adaptation aftereffects may be a manifestation of a normative and beneficial process.

“The nervous system uses adaptation to adjust the range of stimuli it is most sensitive to,” adds Jonathan Winawer, another senior author and an assistant professor of psychology. “Prolonged exposure to a stimulus usually means a higher chance of observing similar stimuli. Our decision-making adjusts to this expectation, amplifying behavioral effects of changes in sensory neurons.”

These adjustments increase our ability to discriminate the most expected stimuli while also reducing our reaction times. However, they can also cause aftereffect illusions for stimuli dissimilar to the adaptor.

To quantify the role of the decision-making system in adaptation, the researchers focused on facial expression aftereffect. Human participants viewed facial images of a single person whose expressions spanned from happy to sad, then reported the expression.

The scientists compared participants’ choices and reaction times against predictions of decision-making models. The combination of choice and reaction times showed that in addition to sensory changes, adaptation also affected the decision-making process itself.

Additional researchers from NYU and Stanford University contributed to the study. A National Institutes of Health grant, an NIH National Research Service Award training grant, a Simons Collaboration on the Global Brain grant, and a McKnight Scholars Award funded the work.

Source: New York University