The rapid spread of very strict abortion bans in some states are leaving health care workers in increasingly difficult positions as they try to care for patients, say three physicians.

States that enacted abortion bans following the US Supreme Court’s recent overturning of Roe v. Wade have not adequately considered the complexity and nuance required of pregnancy care, the physicians say, adding that they expect maternal morbidity rates to increase.

These health experts spoke to journalists Tuesday in a virtual media briefing. A video of the briefing is above.

Here are excerpts:

States with very strict bans on abortion

“We know the patients in these situations are in grave danger. With the passing of the laws in Texas, it’s a very strict ban with a very narrow exception for saving the life of the patient,” says Beverly Gray, associate professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Duke School of Medicine, and founder of the Duke Reproductive Health Equity and Advocacy Mobilization team.

“Essentially they were having to watch those patients until they were on the brink of a catastrophic outcome, and then they could take care of them.”

“That makes it complicated for physicians who are just trying to do the right thing. They’re trying to give their patients the best advice, the best evidence-based care. And that’s being limited.”

“Many of these bans across the country, we see they seek to prosecute physicians. They seek to scare physicians so that they’re not taking care of patients in an evidence-based way. That’s just corroding the trust patients have with their physicians.

“What’s really disheartening is just how quickly these laws are changing, how fast it’s moving, how quickly patients are being affected all over the country.”

“How do we tell if someone’s sick enough? It’s really hard to say in each individual situation what constitutes enough illness. Do you need one organ failing? Do you need two organs failing? Do you need to be to the point where you’re bleeding, where you need a blood transfusion?”

“Patients are confused. Physicians are confused. Ethicists, lawyers are getting involved in care. That’s just clouding the issue and creating a situation where we’re offering worse care for patients.”

Patient concerns and demand for contraception

“I have certainly heard more interest from women lately about having tubal ligations rather than relying on things like IED or implant, things we consider long-term, reversible contraception so a woman can change her mind in a few years and decide to get pregnant,” says Megan Clowse, a rheumatologist with Duke Health and an associate professor in the department of medicine at the Duke School of Medicine.

“I am hearing women who are afraid of having something bad happen to them during a pregnancy to the point where they’re willing to sacrifice their desire for future children even though they’re not entirely sure they don’t want children.”

“We are beginning to have conversations with our patients who are on medications with a risk for long-term birth defects.”

Maria Small, maternal and fetal medicine specialist and associate professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Duke, says, “Many of my patients are asking, ‘If something is seen, how soon do I have to make a decision if there’s something major wrong with my baby and I may not want my baby to live with a major birth defect and a severely compromised quality of life?’ These are decisions that individuals make on a regular basis. When they have a change in guidelines where those decisions need to be made earlier, it becomes more challenging and it becomes more painful. No one can say for sure what they would do in the circumstance many are put in.”

“Having those options—the option of ending a pregnancy—needs to be available to individuals who need it.”

“We are in a maternal health crisis in the United States. We already are dealing with trying to help providers and patients know the warning signs for pregnancy-related conditions that need to be acted upon.”

“You have conditions where legislators are determining when you can and can’t act on condition in pregnancy. This is not their role. And many of them have shown us over and over again by their statements have no clue about pregnancy and women’s health.”

“It really is sad and disturbing that we are fighting so hard to decrease maternal mortality rates and yet we have conditions where people are wondering, ‘Can I intervene in this condition that usually is associated with maternal death, like an ectopic pregnancy?'”

Rise in the birth rate

“[What] I don’t think we’re prepared for nationally is an increase in birth rate. We’re already seeing rural hospitals closing,” says Gray.

“That’s another thing that, as medical providers across the country, we need to start thinking about how to prepare for more pregnancies.”

“We’re already seeing predictions that maternal mortality will increase in states where it’s already high. Many of those states that have high maternal mortality rates also have very strict abortion bans.”

“I think we need to be prepared for the future of obstetrics in our country.”

Abortion bans and rheumatology

“Women with rheumatic disease, which is a large collection of autoimmune diseases in which the immune system is attacking a woman’s own body, can have a lot of complications during pregnancy,” says Clowse.

“We see high rates of pregnancies lost, preterm birth, stillbirth, preeclampsia, and severe health consequences both short term and long term for both the mother and the baby.”

“Abortion bans really change the landscape of rheumatic care for women of reproductive age. Not just the women who are pregnant or want to be pregnant, but all women of reproductive age because so many of our medications either can, we know, impact pregnancy with complications, or might.”

“Some of our most commonly used medications, bedrock rheumatology medications […] are known to increase birth defects when there’s first trimester exposure. I’m particularly concerned the use of these medications is going to decrease in women of reproductive age who are not trying to get pregnant, leading to increased medical complications and disability, organ failure, and in some situations, premature death.”

Abortion bans and heart health

“So many cardiac diseases can result in a much higher risk of death in pregnancy. So sometimes individuals who are pregnant, with a cardiac condition, need to have the option to terminate a pregnancy, to end a pregnancy, as a life-saving action for themselves,” says Small.

“In general, we know the safety of abortion relative to carrying a pregnancy to term is something that’s very important. People don’t necessarily realize there’s a 14-times higher risk of carrying a pregnancy to term in general compared to a termination of pregnancy, an abortion.

“This is just part of women’s health care, care for pregnant individuals and postpartum individuals, that people don’t seem to be taking into account in this banning of this very important part of reproductive care.”

Complicated health care

“There are a whole host of medical conditions that impact people of reproductive age. Until people have an understanding of what individuals are facing, it’s really hard to comprehend,” says Gray.

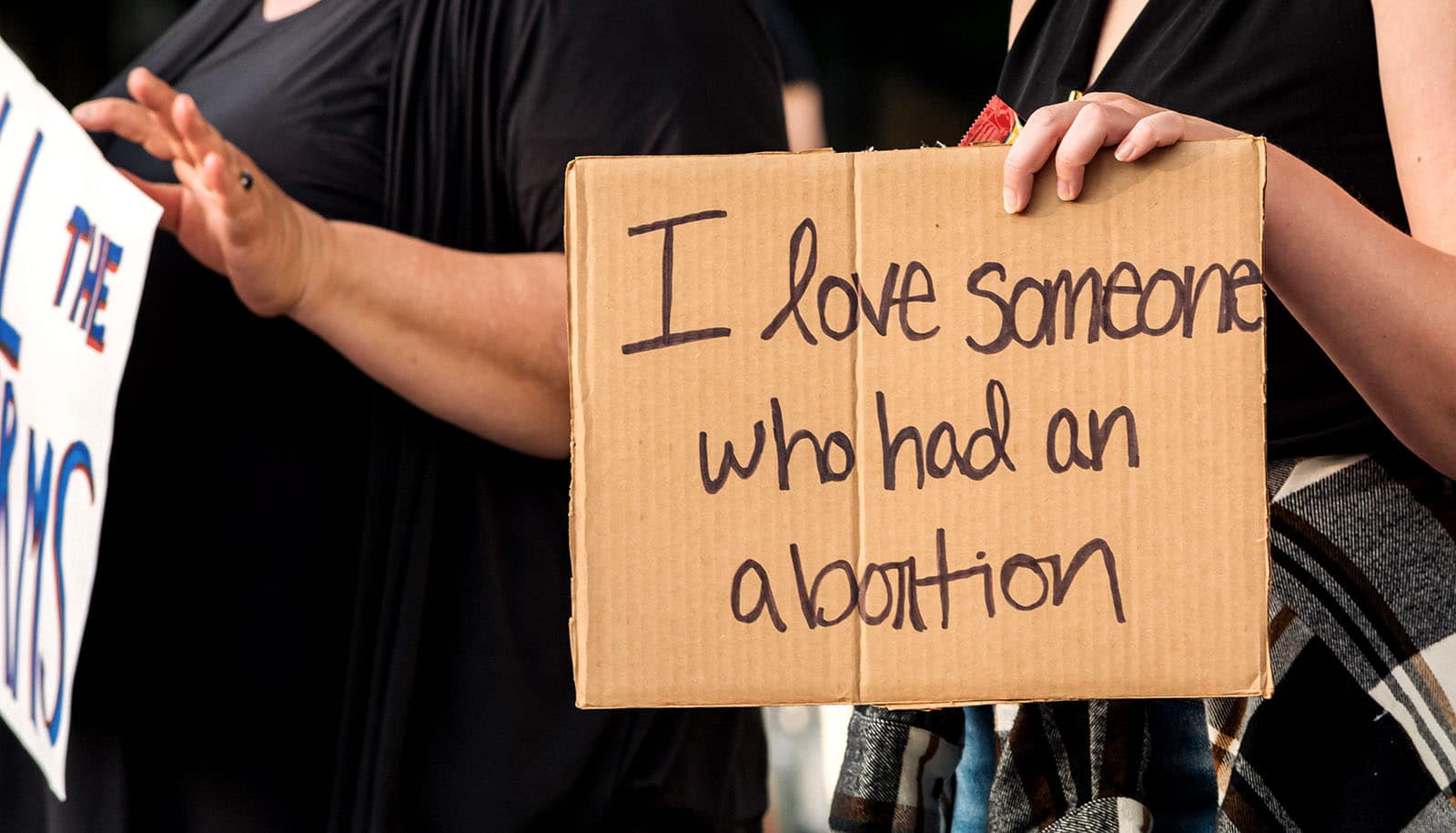

“We all know or care for someone or love someone who’s had an abortion. I think when we’re allowed that window into people’s lives and understanding what they’re facing, we’re able to understand how decisions are made, how folks are approaching their lives and their futures.”

When is the pregnant person’s life in danger?

“Pregnancies that threaten the life of a woman with rheumatic disease are surprisingly common,” says Clowse. “I probably see one or two women a year who conceive when their rheumatic disease is active to an extent that could lead to kidney damage or damage to another organ or can drive up her blood pressure dangerously high and put her at risk for stroke or a heart attack.

“Often at the same time that the woman’s health is in danger, the pregnancy itself, the developing fetus, is also at very high risk for a very early delivery. Sometimes before it is viable and can survive outside the womb and sometimes in the first weeks of viability when it will require months in the intensive care nursery and likely, if they make it out alive, have long-term permanent consequences.

“These conversations with patients are really challenging. It’s not like a woman can walk in really early in pregnancy and I can say, ‘You for sure are going to have a catastrophic outcome.’

“Where do you personally draw the line? Of your safety? Your ability to mother your existing children? Your ability to survive this pregnancy versus your desire to continue this specific pregnancy? How they weigh this specific pregnancy that will likely end in catastrophe versus a potential future pregnancy that could be very well planned and lead to a very successful delivery.

“There’s a lot of nuance that physicians and patients really take very seriously. These are long conversations. These are hard conversations. These are conversations in which women involve their spouse. Involve their families. Involve their priests and pastors and other people who can really help guide them through these life-changing decisions. Different women pick different things.”

‘Late-term’ abortion isn’t a real term

“A ‘late-term abortion’ is not a medical term,” says Gray. “It’s not a term that we physicians use. It’s a term that’s very politicized, that politicians use to make it appear that the vast majority of abortions are happening in the late second, third trimester. Which is absolutely not the case. We know the vast majority of abortion care that occurs in our country happens in the first eight weeks of pregnancy. Only 1.2% of care happens after 20 weeks, and that’s typically before viability. It’s right around the 20th week. In North Carolina that rate is even lower.

“Those are the cases politicians want to talk about, that there’s this care happening right at term pregnancy. That’s not the case.

“We take care of very sick, medically complicated patients all the time here in our institution. Many of those patients, they want to continue their pregnancies. They want to have hope for those pregnancies. We give them that hope.

“Throwing around that term is kind of dangerous. I think politicians are trying to be doctors and using non-medical language to make it seem like something nefarious is happening. Which is not the case.”

Medication abortion and self-managed abortion

“Women who terminate, who do medical terminations at home and don’t let their doctor know—particularly in states where this might be illegal, I think that women are not going to be forthcoming with their providers, we will not really understand their risk landscape when they’re calling,” says Clowse.

“We’re not going to know how to help them have a successful pregnancy in the future. So I do think that’s risky and problematic.”

Too little care?

“I think physicians are concerned about that,” says Clowse. “We go into becoming doctors in order to help our patients live the best lives that they can. Sometimes that means talking about abortion and helping patients access abortion. I think doctors are concerned that they’re not going to have the ability to do that for their patients, and that could lead to legal consequences for them. There’s a lot of talk in the other direction, but I think it’s important that we remember that when we provide substandard care to our patients, we do them a disservice and that puts all of us at some risk.”

Inequities in reproductive health

“The whole idea that people being afraid they may be criminalized if they’re seeking out abortion care, even if they’re seeking out support related to how to self-manage termination,” say Small.

“You have a scenario where people who may, because of previous injustices in the health care system, or previous mistrust of the health care system, are contributing to some of the maternal mortality in the United States. And you have a scenario where you’ve placed individuals in an adversarial position that may even involve law enforcement. That’s a very dangerous situation for communities of color.

“This environment of placing pregnant and potentially pregnant individuals in this kind of toxic relationship with health care providers is one that is only going to worsen maternal mortality […] for Black women in America.”

Miscarriage care

“The medications that we use for miscarriage management are absolutely the same as the ones we used for medication abortion care,” says Gray.

“The process of someone’s body having a miscarriage versus going through the normal process of medication abortion, there’s no litmus test that you can say, ‘Oh, this patient had a miscarriage, or not.’

“That worries patients. They wonder, will doctors know what’s going on with my body? Will they test me for these medications? It doesn’t even matter because those are the same medications we use for miscarriage.”

Mental health and maternal deaths

“Mental health. This is an area that is garnering, appropriately, additional attention in our country,” says Small.

“Severe maternal morbidity is associated with a higher risk for maternal conditions like depression and even Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. These are things that are life-threatening, that don’t cause death, but they would cause death if they weren’t treated.

“You’re asking individuals to be pushed to the brink of death […] because a legislator has deemed that be the case. That is something that really concerns me, it troubles me.

“I think we just have no sense of just how bad this is going to impact individuals in our country.”

The future of ob-gyn care

“In states like Texas and others that already had a strict ban in place, they’re seeing how those changes are happening right before their eyes,” says Gray. “They’re seeing patients’ lives being put at risk on a daily basis. They’re having to give patients non evidence-based advice and recommendations because their state legislators are saying that’s the right thing to do.

“You don’t know what a patient is experiencing or going through. You can’t imagine it until you’re facing it yourself. That trust between a patient and their physician or their health care provider needs to be reinstated. There’s this idea that a ban will make care safer for the patient—that’s absolutely not true at all. In fact it makes care less safe. It will likely increase maternal mortality in this country.

“It’s not just a simple question of right or wrong. This is a complicated issue and people feel differently about it, but we have to let patients have autonomy over their lives.”

Source: Duke University