A surge in childhood food allergies across the United States has turned classrooms into homemade-treat-free zones and parents into experts at scanning labels. But what’s fact and what’s fiction?

Ruchi Gupta has been at the forefront of food allergy research, applying her findings both in her clinical practice and in her home. After Gupta began her career, her daughter was diagnosed with peanut, tree nut, and egg allergies. The impact of that diagnosis, and the struggle to separate fact from fiction, cemented Gupta’s drive to understand more about allergies, help families cope, and empower food allergy sufferers to lead full, fearless lives.

Part of that work, she explains, means debunking some of the myths and misconceptions about food allergies. Gupta, a professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, acknowledges that while there is still much more to learn—and she’s leading some of that path-breaking research—there are things we do know.

Below, Gupta explains some of the most common misconceptions about food allergy prevalence, impact, and prognosis for patients.

1. Food allergies are rare and aren’t often serious

Eight percent of children in the US—or 6 million kids—have at least one food allergy. That means 1 in 13 children—two kids in every classroom—must avoid certain foods.

And those allergies can be fatal. In fact, 40 percent of children with food allergies have suffered a life-threatening reaction, Gupta says.

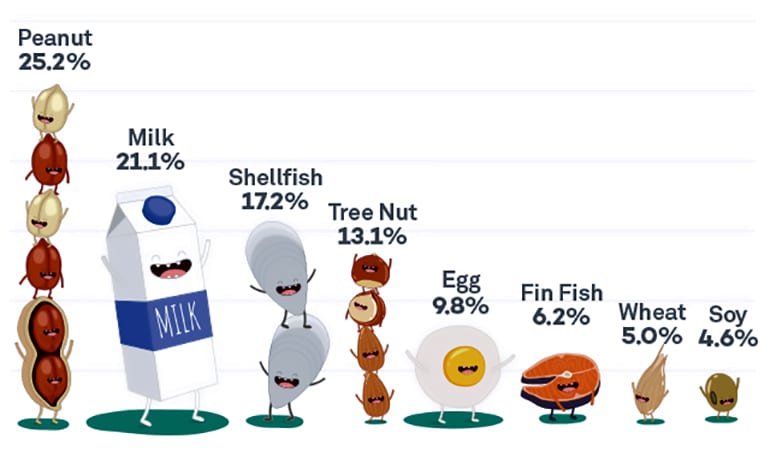

Nine items account for the vast majority of food allergies: peanuts, eggs, milk, soy, wheat, tree nuts, fin fish, shellfish, and sesame, all foods that can be hard to avoid in grocery stores and restaurants.

2. Food labels make it easy to know what’s safe for people with food allergies

Food labels can be a minefield. Manufacturers are required to identify the presence of the top allergens in their products, but “precautionary” allergen labeling is voluntary and unregulated.

“Precautionary labeling includes ‘may contain’ and ‘manufactured on equipment that processes…,'” Gupta says. “A lot of companies are adding these, and that’s tough for families who have no way of knowing if products with these labels are safe.”

Avoiding foods with any allergen labeling is only an option for families who can afford to buy specially marked, allergen-free products. “Often, many families take chances because almost everything has one of those precautionary allergen labels on it,” Gupta says.

3. Eating a little bit of a food won’t hurt

Giving a food-allergic person a small amount of the food they’re allergic to will not necessarily reduce the allergy and can be extremely dangerous, even deadly.

But, Gupta says, feeding peanut products early to all infants around 6 months can help reduce the odds of developing a peanut allergy. Gupta coauthored new guidelines, endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics, recommending this careful dosing of peanut products to infants as a means of reducing peanut allergies.

This practice requires risk assessment by a pediatrician, Gupta says. If a child has severe eczema or egg allergy, both of which place them at high risk for peanut allergy, parents should first introduce peanuts to their child in an allergist’s office.

4. Food allergies mostly impact high-income, white families

Research shows food allergies affect families across all income levels and racial and ethnic backgrounds.

“In our prevalence study, we found that African-American and Asian-American children actually had higher rates of food allergy but lower rates of being diagnosed,” Gupta says. “Interestingly, we also found low-income kids had lower rates of food allergy and lower rates of being diagnosed.”

“It’s often hard to understand how food, which we need to live, could hurt you.”

Additionally, low-income families are more dependent on costly emergency care, spending 2.5 times more on hospitalizations and trips to the emergency department. Low-income families often lack access to specialty care and allergen-free foods that could prevent dangerous allergic reactions.

Gupta is now looking into the lower diagnosis rates. It could be that low-income parents simply avoid feeding their children foods they’ve reacted to in the past, without seeing a doctor to test for allergies.

“We’re looking at the Medicaid database to see what happens to kids—how they’re getting diagnosed with food allergies, and then how many of them are getting follow-up care from an allergist,” she says. “We want to know what prescriptions they’re getting and what kind of tests are being done.”

5. Beyond avoiding certain foods, there’s not much that can be done to help kids with food allergies

There are several proactive steps families can take in addition to getting rid of unsafe foods.

For example, families should explain the allergy to everyone who helps care for their child. It’s important, to make sure everyone understands what to do in case of an emergency, the signs of an allergic reaction, and how to use an epinephrine auto-injector.

Are baby wipes and dust key ‘ingredients’ for food allergies?

“Beyond that, one of the biggest things parents can do is connect with others,” Gupta says. Parent groups also help kids with food allergy connect with kids like them. Children can feel anxious or isolated as a result of their food allergies: Some are bullied for their food restriction, while others don’t know how to explain their allergies to friends.

“It’s often hard to understand how food, which we need to live, could hurt you,” Gupta says. “It’s critical that we help friends and family members understand how real food allergies are.”

Source: Northwestern University