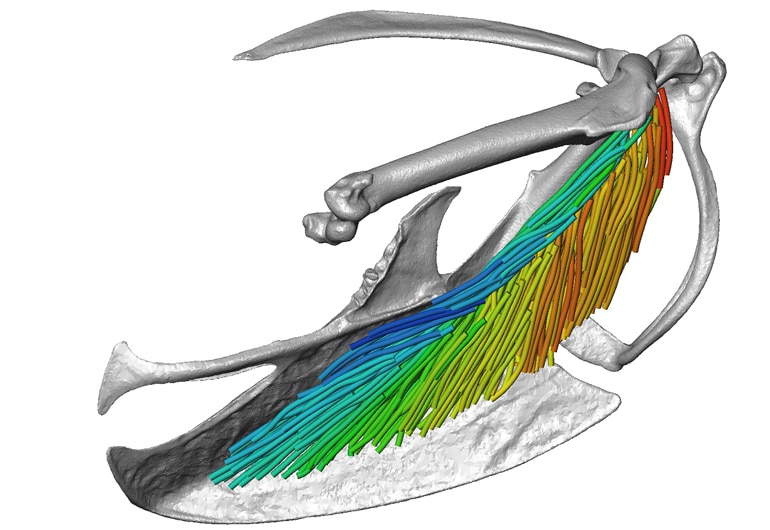

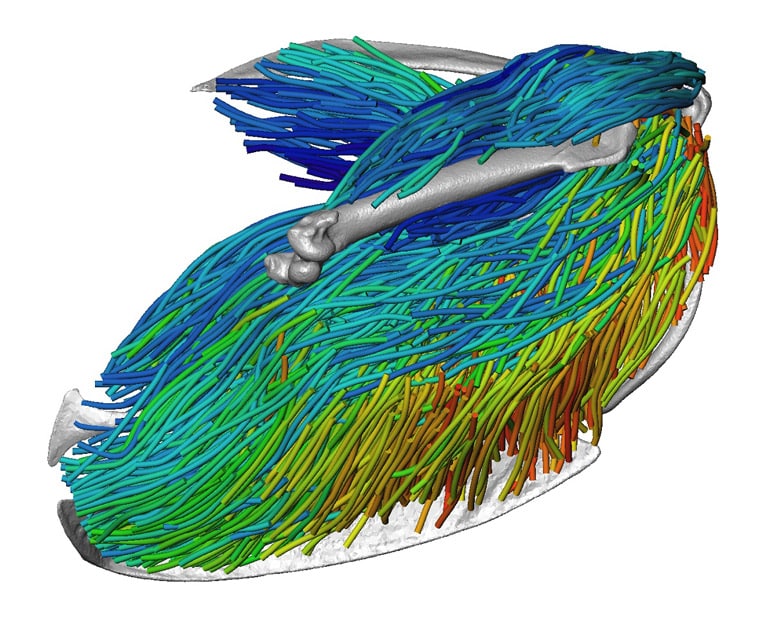

A 3D model of the skeletal muscles responsible for bird flight provides the most comprehensive and detailed picture of anatomy to date, researchers say.

The study will form the basis of future research on the European starling’s wishbone, which these particular muscles support. Scientists hypothesize the wishbone bends during flight.

“A lot of people have looked at this on a larger scale, but not in the detail we acquired,” says Spiro Sullivan, a doctoral student in the School of Medicine at the University of Missouri and lead researcher of the study, which appears in Integrative Organismal Biology: A Journal of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology.

“It’s an unprecedented look into an especially tiny animal that bridges the gap between microscopic and large-scale muscle function.”

The researchers used an Xradia X-ray microscope to collect the data and create a three-dimensional model of the bird’s muscle fibers.

“We’re using a mixture of enhanced CT imaging scans in combination with this new visualization technique of 3D muscle fiber architecture,” says Casey Holliday, an associate professor in the School of Medicine.

“It’s one of the first biological uses of this particular microscope, which can help us see inside animals in ways we could never before. This 3D model can be displayed virtually on phones or with virtual reality goggles, or through a printed 3D model.”

The new technology can support various fields such as health sciences, medical education, research in biomechanics, paleontology, evolutionary biology, and public education, the researchers say.

“This new technology is a great teaching tool on how humans and animals work at any educational level,” says Kevin Middleton, an associate professor in the School of Medicine. “We already had a pretty good understanding of muscles on a broader level but until now we didn’t have a good way to see where the basic function of a muscle is happening.”

Coauthor Faye McGechie, a doctoral student and Life Sciences Fellow. is applying the technology to understanding human evolution. “Many primates are endangered, and they have muscles that we have not been able to visualize yet because they are either too small or understudied,” she says.

The National Science Foundation, the University of Missouri Life Sciences Fellowship program, the University of Missouri Research Board, and the University of Missouri Research Council funded the work. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Source: University of Missouri