This year’s winter solstice will take place Thursday December 21, in the Northern Hemisphere, while the Southern Hemisphere experiences its summer solstice.

Because the Earth’s axis is tilted farthest from the sun, winter solstice is the darkest, shortest day of the year.

“Similar to our fascination with nature and science, for them the solstice and tracking the sun was about creating an understanding of the order of the universe.”

Around the world, people celebrate the winter solstice. China’s Dongzhi (literally “the extreme of the winter”) Festival celebrates the winter solstice, along with the imminent return to longer days. At the ancient ruins of Stonehenge in England, thousands gather before sunrise to celebrate. In Japan, some partake in a traditional hot bath, soaking with a Japanese citrus fruit, called yuzu, to greet the winter solstice while protecting against common colds.

But human interest in the movements of the sun is far from new. Perhaps in no civilization was it more important than with the Maya, explains Takeshi Inomata, a professor of anthropology at the University of Arizona. Inomata’s archaeological research focuses on Maya civilization.

Prior to Spanish conquest in the 16th century, Maya civilization prospered in southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and western Honduras. The Maya are known primarily for their elaborate constructions, including pyramids and palaces, and their writing system, which was the most sophisticated in the New World.

Complex calendars

“The Maya were fascinated with time and the movement of celestial bodies, and the calendar is a major part of their writing system,” Inomata says.

The two main Maya calendars were the Long Count calendar and the Calendar Round.

The Long Count starts with a fixed date in 3114 BCE and is based on a 360-day year. It is organized in a 20-year cycle, and at the completion of each cycle the Maya held a large ceremony to celebrate the passage of time. Larger cycles consist of 400 years and 5,200 years. The latter cycle completed on the winter solstice of December 21, 2012, which some feared would represent the end of the world. However, the Maya never talked about this completion date in apocalyptic terms.

The Calendar Round, on the other hand, is a 365-day solar calendar combined with a 260-day cycle. After 52 years, the Calendar Round returns to the original combination of days, and a new cycle begins.

Without tracking the movements of the sun, Inomata says, the Maya would not have been able to create the complex, precise calendars that they did.

“The Maya really made a point of tracking the movement of the sun,” Inomata says. “And the solstice would have been the most important fixed point for the creation of their calendar system.”

The Maya used their calendar system to record historical events with unprecedented precision.

Maya temples

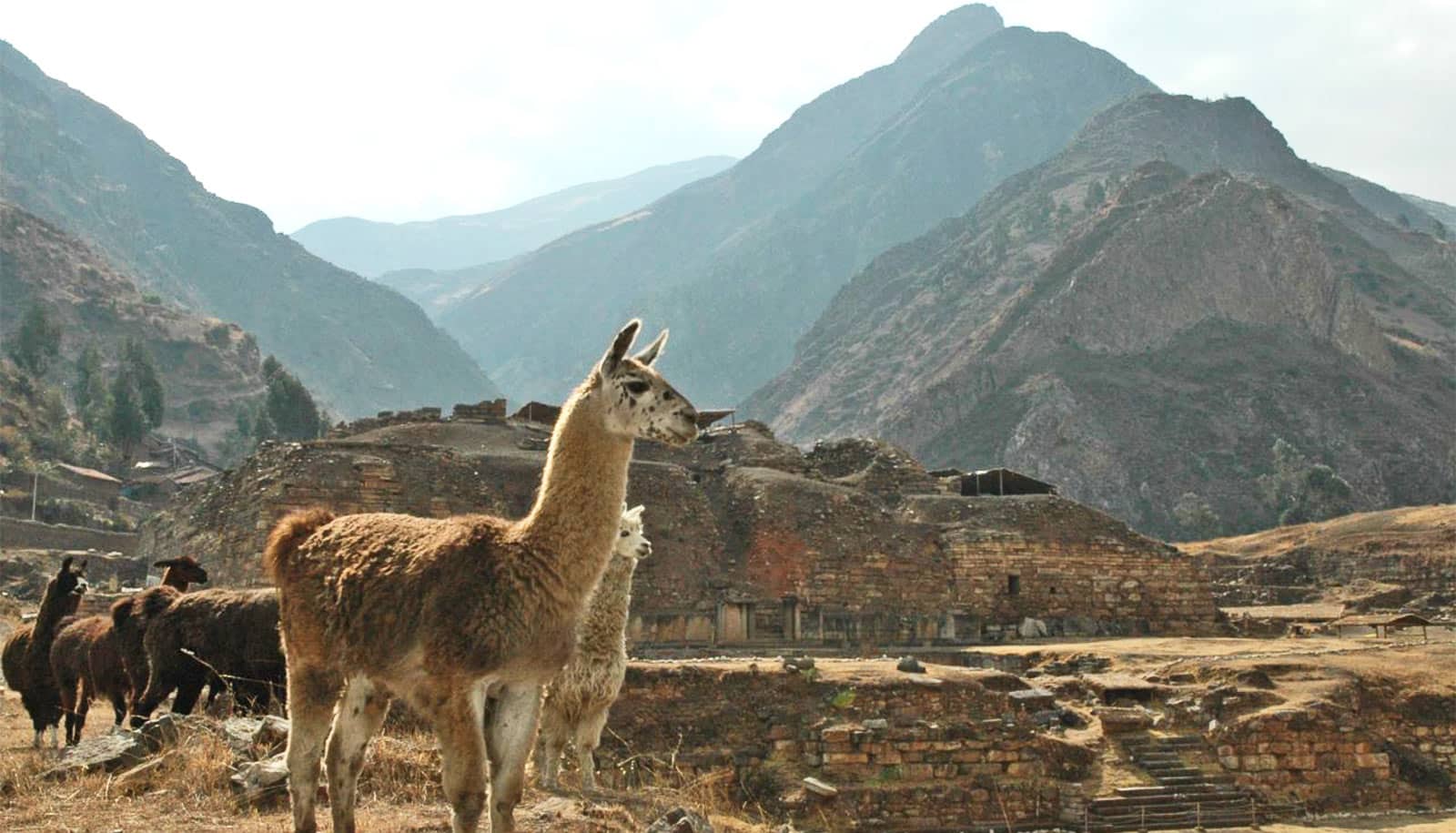

The Maya also built entire ceremonial complexes that were positioned specifically for the celebration of the solar cycle. At a site called Uaxactun in Guatemala, the ancient ruins of a Maya ceremonial complex illustrate the stunning precision of the Maya.

A pyramid on the western side of the complex faces a raised, elongated structure with three temples on the eastern side. The northern temple was built to observe the summer solstice, the southern temple was for the winter solstice, and the temple in the center was for the equinox. All three are aligned precisely so that, during these solar phenomena, half of the pyramid appears in light while the other half is in darkness.

6 ways ancient Maya still alter the environment

Research by Inomata and his team at the Maya site of Ceibal, Guatemala, discovered the earliest known solar temple complex, dating to 1000 BCE.

Inomata notes that, just as our maps are drawn with north facing upward, Maya maps put east facing upward—another reminder that the east-west directionality of the sun was significant to this civilization.

Sun as deity

For the Maya, an awareness of the sun’s movements went even deeper than the desire to understand and record the passage of time. It was religious.

“The sun was a deity—almost a sort of living creature,” Inomata says.

In Maya mythology, the sun god would rise every day, go down to the depths of the sea, into the belly of a monster, and rise back up again the next day. Tracking his movements was important.

Because this god, called K’inich Ajaw by the 16th-century Yucatec Maya, represented a critical element of the world, as a provider of light and life, rulers sometimes would try to connect themselves to the sun god.

“They would take the facial features from the sun god and put them on themselves,” Inomata says. For example, a king might put on a mask or headdress to mimic K’inich Ajaw’s appearance.

Bones hint at lives of Maya middle class

The Maya often laid out offerings for the celebration of the calendrical cycle, such as jade axes, along the central axis of a solar temple complex.

Today’s celebrations of the winter solstice may be much more focused on the notion of seasonality, but Inomata reminds us that the driving force behind the Maya rituals is not all that different from ours, in some ways.

“Similar to our fascination with nature and science, for them the solstice and tracking the sun was about creating an understanding of the order of the universe,” he says.

Source: University of Arizona