New research suggests that parasitic infections could increase in the next century due to rising sea levels caused by climate change.

In 2014, a team of researchers found that clams from the Holocene Epoch (that began 11,700 years ago) contained clues about how sea level rise due to climate change could foreshadow a rise in parasitic trematodes, or flatworms. The team cautioned that the rise could lead to outbreaks in human infections if left unchecked.

Now, researchers have found that rising seas could be detrimental to human health on a much shorter time scale.

Trematodes are internal parasites that affect mollusks and other invertebrates inhabiting estuarine environments, which are the coastal bodies of brackish water connecting rivers to the open sea. Ancient trematodes had soft bodies; therefore, they didn’t leave body fossils. However, infected clams developed oval-shaped pits around the parasite in the attempt to keep it out, and it’s the prevalence of those pits and their makeup that provide clues as to what happened during different eras in time.

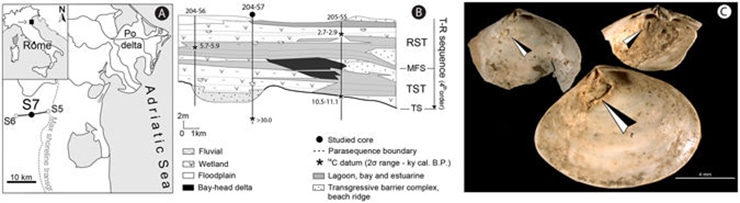

With core samples taken from the Po River plain in Italy, geologist John Huntley, and colleagues found traces made by trematodes on the shells of the clams, revealing the connections between the ancient clams and climate change. Huntley, an assistant professor of geological sciences in the University of Missouri College of Arts and Science, studied the prehistoric clams as a senior visiting fellow for the Institute for Advanced Studies at the University of Bologna, Italy.

“The forecasts of increasing global temperatures and sea level rise have led to major concerns about the response of parasites to climate change,” he says. “Italy has a robust environmental monitoring program, so there was a wealth of information to examine.”

“What’s scary is it could potentially affect the generations of our kids or grandkids.”

Using 61 samples collected from a drill core obtained by the Italian government for geological research, the scientists examined trematode traces and matched the information to existing records measuring sea level and salinity rises through the ages.

“We found that pulses in sea-level rise occurred on the scale of hundreds of years, and that correlated to rises in parasitic trematodes in the core samples,” Huntley says. “What concerns me is that these rises are going to continue to happen and perhaps at accelerated rates.

“This poses grave concerns for public health and ecosystem services. These processes could increase parasitism in not only estuarine systems but also in freshwater settings. Such habitats are home to the snail hosts of blood flukes, which infect and kill a million or more people globally each year.

“What’s scary is it could potentially affect the generations of our kids or grandkids,” he says.

Huntley and his team think that their discoveries could provide a good road map for conservationists and those making decisions about marine environments worldwide.

The study appears in Scientific Reports. National Science Foundation grants, the Institute of Advanced Studies at the University of Bologna, the Unkelsbay Fund of the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Missouri, and the University of Bologna provided funding for the study.

Additional contributors to the study are from the University of Bologna and the University of Florida. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Source: University of Missouri