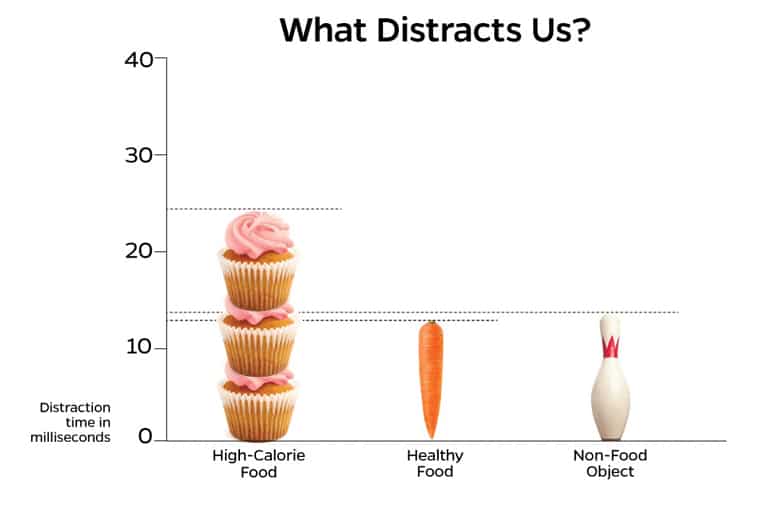

When we’re hungry, pictures of cookies, pizza, and ice cream sidetrack us far more than photos of healthy food do. And that’s even when we’re hard at work.

The good news is that after just a few bites of candy, junk food is no more diverting than kale.

A new study in Psychonomic Bulletin and Review underscores people’s implicit bias for fatty, sugary foods, and provides evidence for the common wisdom that you shouldn’t grocery shop on an empty stomach.

“We wanted to see if pictures of food, particularly high-fat, high-calorie food, would be a distraction for people engaged in a complicated task,” says coauthor Howard Egeth, a professor of psychological and brain sciences at Johns Hopkins University.

“…when we showed them chocolate cake and hot dogs, these things slowed them down about twice as much.”

“So we showed them carrots and apples, and it slowed them down. We showed them bicycles and thumbtacks, and it slowed them down. But when we showed them chocolate cake and hot dogs, these things slowed them down about twice as much.”

First, Egeth and lead author Corbin A. Cunningham, a fellow in psychological and brain sciences, created a complicated computer task; food was irrelevant to getting the task done right. They then asked a group of participants to find the answers as quickly as possible.

As the participants worked diligently, pictures flashed in the periphery of the screen—visible for only 125 milliseconds, too quick for people to fully grasp what they had glimpsed. The pictures were a mix of images of high-fat, high-calorie foods; healthy foods; or items that weren’t food.

All of the pictures distracted people from the task, but things like doughnuts, potato chips, cheese, and candy were about twice as distracting. The healthy food pictures—like carrots, apples, and salads—were no more distracting to people than non-foods like bicycles, lava lamps, and footballs.

Next, the researchers recreated the experiment, but had a new group of participants eat two small “fun-sized” candy bars before starting the computer work.

“What your grandmother might have told you about not going to the grocery store hungry seems to be true.”

The researchers were surprised to find that after eating the chocolate, people weren’t distracted by the high-fat, high-calorie food images any more than by healthy foods or other pictures.

The researchers wonder now if a smaller amount of chocolate—or even other snacks—would would have the same effect.

“I assume it was because it was a delicious, high-fat, chocolatey snack,” Egeth says. “But what if we gave them an apple? What if we gave them a zero-calorie soda? What if we told the subjects they’d get money if they performed the task quickly, which would be a real incentive not to get distracted? Could junk food pictures override even that?”

Does knowing junk food by name raise kids’ obesity risk?

The results strikingly demonstrate that, even when food is entirely irrelevant, and even when people think they’re working hard and concentrating, food has the power to sneak in and grab our attention—at least until we eat a little of it.

“What your grandmother might have told you about not going to the grocery store hungry seems to be true,” Cunningham says. “You would probably make choices that you shouldn’t, or ordinarily wouldn’t.”

Source: Johns Hopkins University