Scientists have discovered additional remains of a new human species, Homo naledi, in a series of caves northwest of Johannesburg, South Africa.

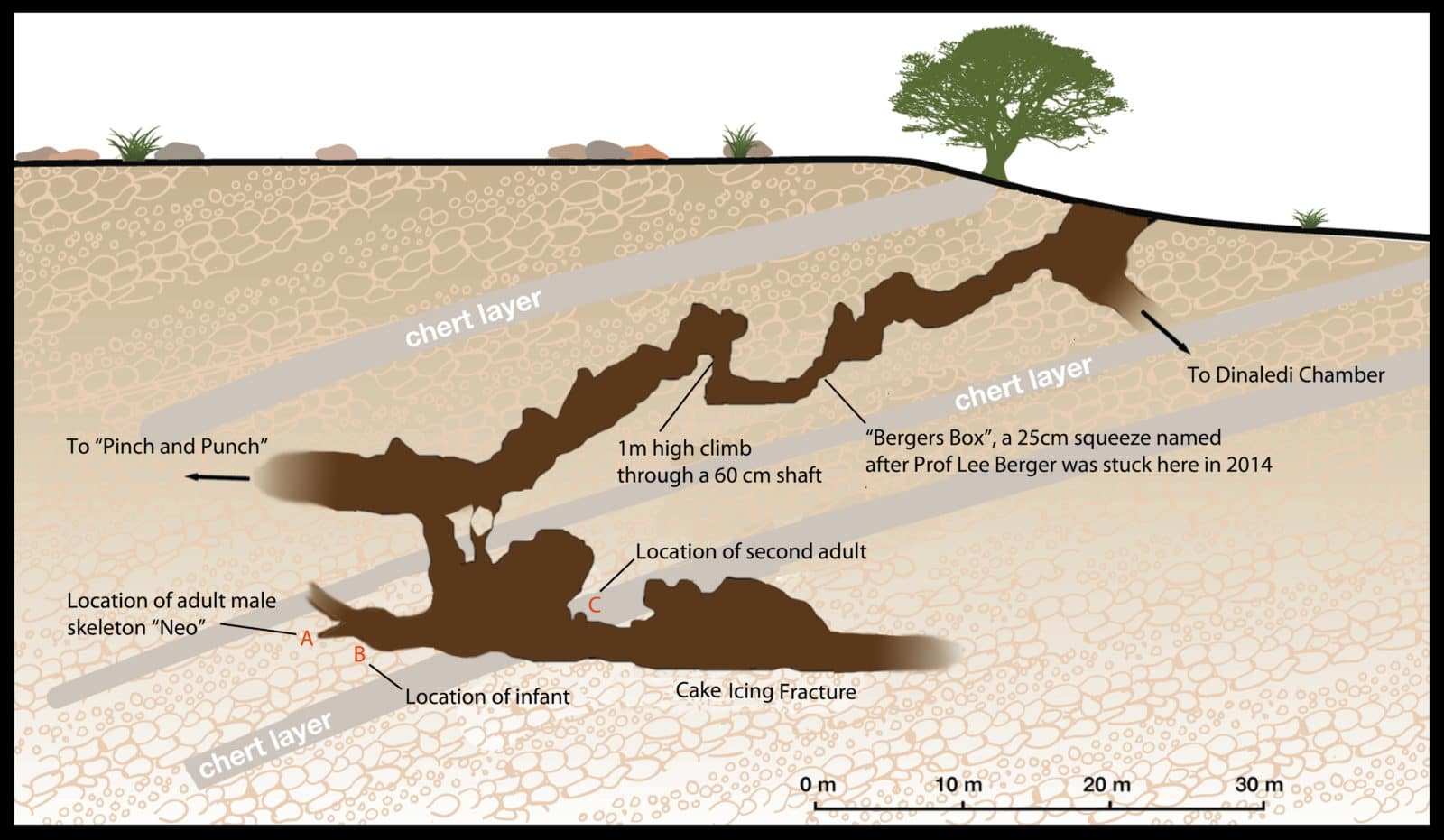

The find, which includes the remains of two adults and a child in the Lesedi Chamber of the Rising Star Cave system, expands the fossil record originally reported from a different chamber of the cave in 2015.

Details of the latest discovery appear in eLife, along with another paper that pinpoints an age range of the original Rising Star fossils, which included 15 different individuals—primitive, small-brained human ancestors believed to be between 236,000 and 335,000 years old. This means that Homo naledi may have coexisted, for a period of time, with Homo sapiens, the species of modern humans.

“We can no longer assume that we know which species made tools, or even assume that it was modern humans that were the innovators of some of these critical technological and behavioral breakthroughs in the archaeological record of Africa,” says Lee Berger at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, who assembled the team that first explored the Rising Star system in 2013 and is an author of the new studies.

“If there is one other species out there that shared the world with ‘modern humans’ in Africa, it is very likely there are others. We just need to find them.”

Researchers haven’t yet been able to date the fossils from the Lesedi Chamber, which include one of the most complete skeletons of an early human found to date. The excavation of that chamber, researchers believe, provides further evidence that this early human species deliberately disposed of its dead in these remote, hard-to-reach caves.

“The process of human evolution is more complicated than we thought.”

That hypothesis generated criticism when the Dinaledi discovery was first reported, with some scientists pointing to other potential causes and timelines for the deposition of the bones. The Rising Star team maintains that the lack of animal remains found at the site, and the absence of injury to or erosion of the human fossils, rules out predatory or natural causes of accumulation.

The Lesedi fossils also shed light on the physical capabilities of Homo naledi, says Elen Feuerriegel, a postdoctoral researcher in the anthropology department at the University of Washington.

Complex evolution

The finds so far indicate a species that walked upright and used its hands for complex grasping—like Homo sapiens—but also had an upper limb structure that was built for climbing, like more primitive humans.

“What we’re seeing is the importance of compromise in our own genus,” Feuerriegel says. “The fact that Homo naledi has a similar hand and wrist to Homo sapiens, but a brain one-third the size of ours, shows that they may not have needed as much brainpower to do complex things. The process of human evolution is more complicated than we thought.”

Cooking gave humans the biggest primate brain

Further excavation of the cave system is planned, an undertaking that requires excavators who can squeeze through passages as narrow as 7 ½ inches and spend hours 100 feet underground.

“We have further proof that Homo naledi intentionally buried their dead…”

The new fossils include the skull of an adult male that is more complete than one found in Dinaledi. The team has named the Lesedi skeleton Neo, and consider it more complete than that of Lucy, the remains of an earlier species known as Australopithecus afarensis that were found in Ethiopia in 1974.

The specimens from Lesedi are similar to those from Dinaledi and are undoubtedly from the same species, says John Hawks, associate professor of anthropology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and an author of all three papers.

Because determining the age of the Lesedi fossils could cause some damage to the remains, researchers expect to begin that process after more fossils are collected. But based on the appearance and condition of the Lesedi fossils, they are believed to fall within the same general time period as those of Dinaledi.

Burying their dead

To establish an age of the Dinaledi fossils, scientists used a combination of techniques for both the bones and the surrounding sediments, including uranium series and electron spin resonance dating to examine teeth. Since other Australopithecus fossils have been found not far from the Rising Star Cave system, researchers had initially expected the Dinaledi fossils to be closer in age to those older ancestors—not from as recently as 236,000 to 335,000 years ago.

For early humans, life was no picnic 1.8 million years ago

The age indicates that Homo naledi may have survived for as long as 2 million years alongside other species of early humans in Africa. In the period in which Homo naledi is believed to have lived, known as the Middle Pleistocene, it was previously thought that only Homo sapiens existed in Africa. That time is also characterized by the rise of what is considered “modern” human behavior in southern Africa, such as the use of complex tools and burial of the dead.

“We have further proof that Homo naledi intentionally buried their dead and the bodies we found in the cave show that they were deliberately placed in the cave soon after death,” says Darryl de Ruiter, professor of anthropology at Texas A&M University.

“Neanderthals and their ancestors—which go back about 400,000 years—and humans are the only species we know that intentionally buried their dead, so this cave adds another species to the list of relatives who participated in this most human of behaviors.”

Source: University of Washington / Texas A&M University