Using a computer model, researchers have uncovered previously unknown details about how HIV “hacks” cells to make them spread the virus to other cells. Their findings may offer a new avenue for drugs to combat the virus.

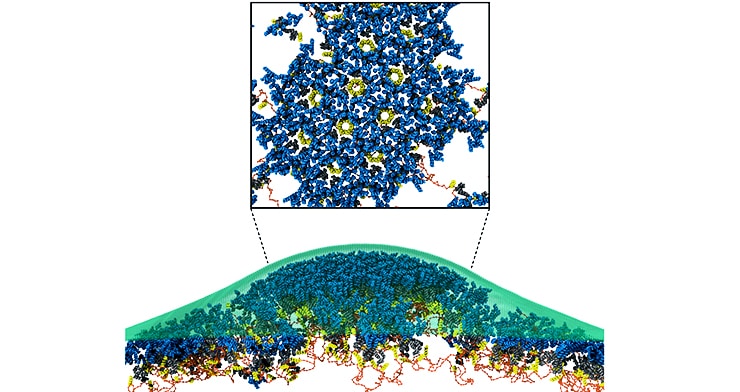

A key part of HIV’s success is a nasty little trick to propagate itself inside the body. Once HIV has infected a cell, it forces the cell to make a little capsule out of its own membrane, filled with the virus.

The capsule pinches off—a process called “budding”—and floats away to infect more cells. Once inside another unsuspecting cell, the capsule coating falls apart, and the HIV RNA gets to work.

Scientists knew that budding involves an HIV protein complex called Gag protein, but the details of the molecular process were murky.

“For a while now we have had an idea of what the final assembled structure looks like, but all the details in between remained largely unknown,” says Gregory Voth, professor of chemistry at the University of Chicago and corresponding author of the paper.

Since it’s been difficult to get a good molecular-level snapshot of the protein complex with imaging techniques, Voth and his team built a computer model to simulate Gag in action.

Simulations allowed them to tweak the model until they arrived at the most likely configurations for the molecular process, which experiments in the laboratory of Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz at the National Institutes of Health and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Janelia Research Campus then validated.

Potential HIV vaccine works in a new way

They built a model of missing parts of the Gag protein complex, and tweaked it until they could see how the proteins assemble by taking advantage of cellular infrastructure in preparation for the budding process.

“It really demonstrates the power of modern computing for simulating viruses,” Voth says.

“The hope is that once you have an Achilles’ heel, you can make a drug to stop Gag accumulation and hopefully arrest the virus’s progression.”

The team plans next to study the structures of the Gag proteins in the HIV virus capsule after budding, he says.

Is HIV cured or still lurking? New test can say

The researchers report their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Source: University of Chicago