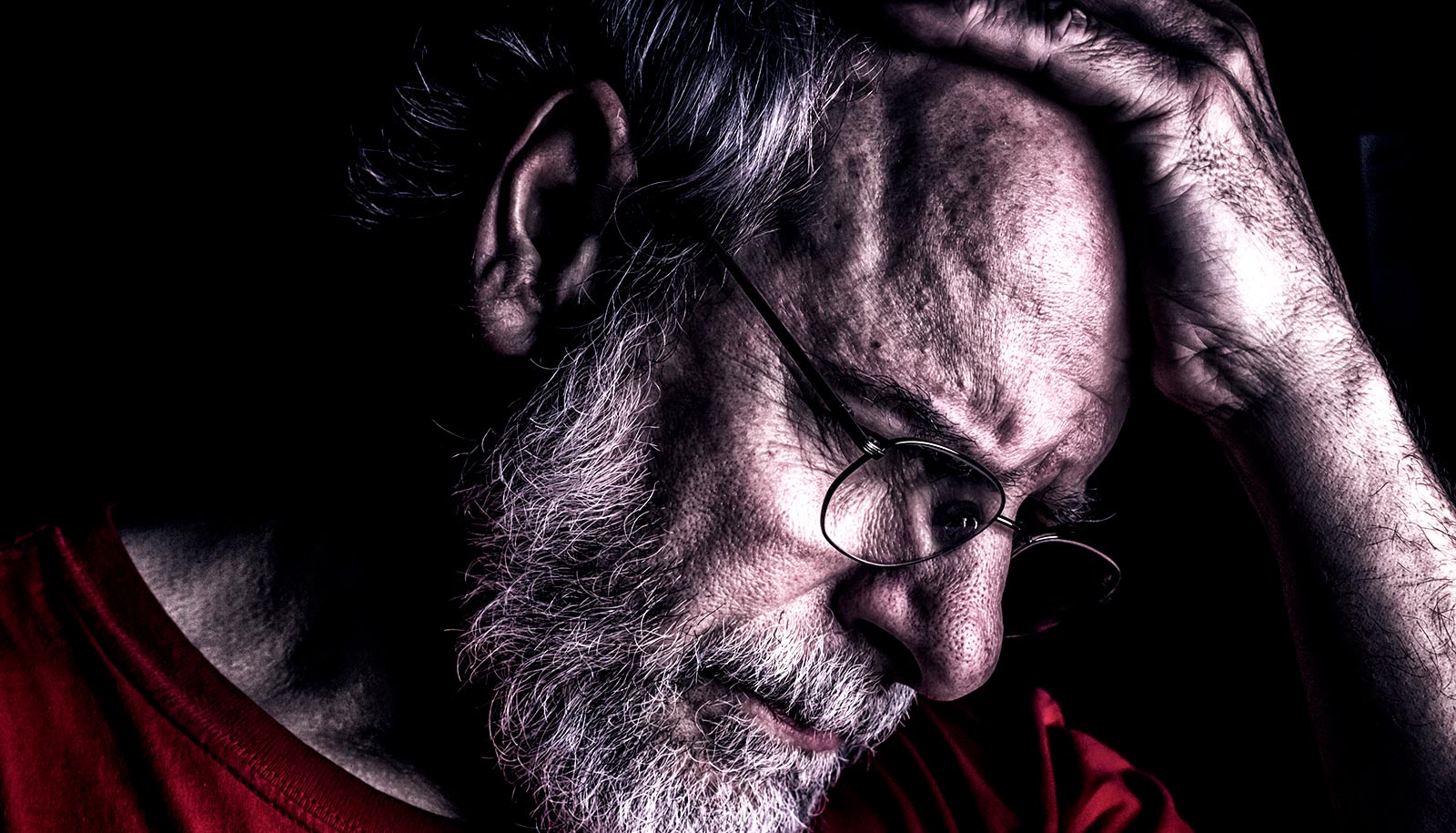

Being diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor is devastating news for patients and their loved ones. While some types of tumor respond well to treatment, others such as glioblastomas—the most common and aggressive brain tumors—recur and progress within short times from the diagnosis.

Patients diagnosed with this type of cancer, and who undergo current standard treatment, have a median survival of 16 months.

Now, researchers have developed a new clinical approach to increase the efficiency of treatment in glioblastomas that increased the median survival to 22 months. The findings of the phase II clinical trial appear in the International Journal of Radiology Oncology.

“Glioblastomas are very difficult to treat,” says George Shenouda, radio-oncologist at the McGill University Health Centre and lead author of the study. “These tumors grow and spread quickly throughout the brain, making it very difficult to completely remove with surgery.”

This protein flags the worst glioblastomas

The standard treatment for glioblastomas includes removing as much of the tumor as possible with surgery and then eliminating what is left through radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy. After surgery, patients need at least four-to-five weeks of recovery before starting radiotherapy.

“50% of the patients in our study have survived two years since their diagnosis. This is very encouraging…”

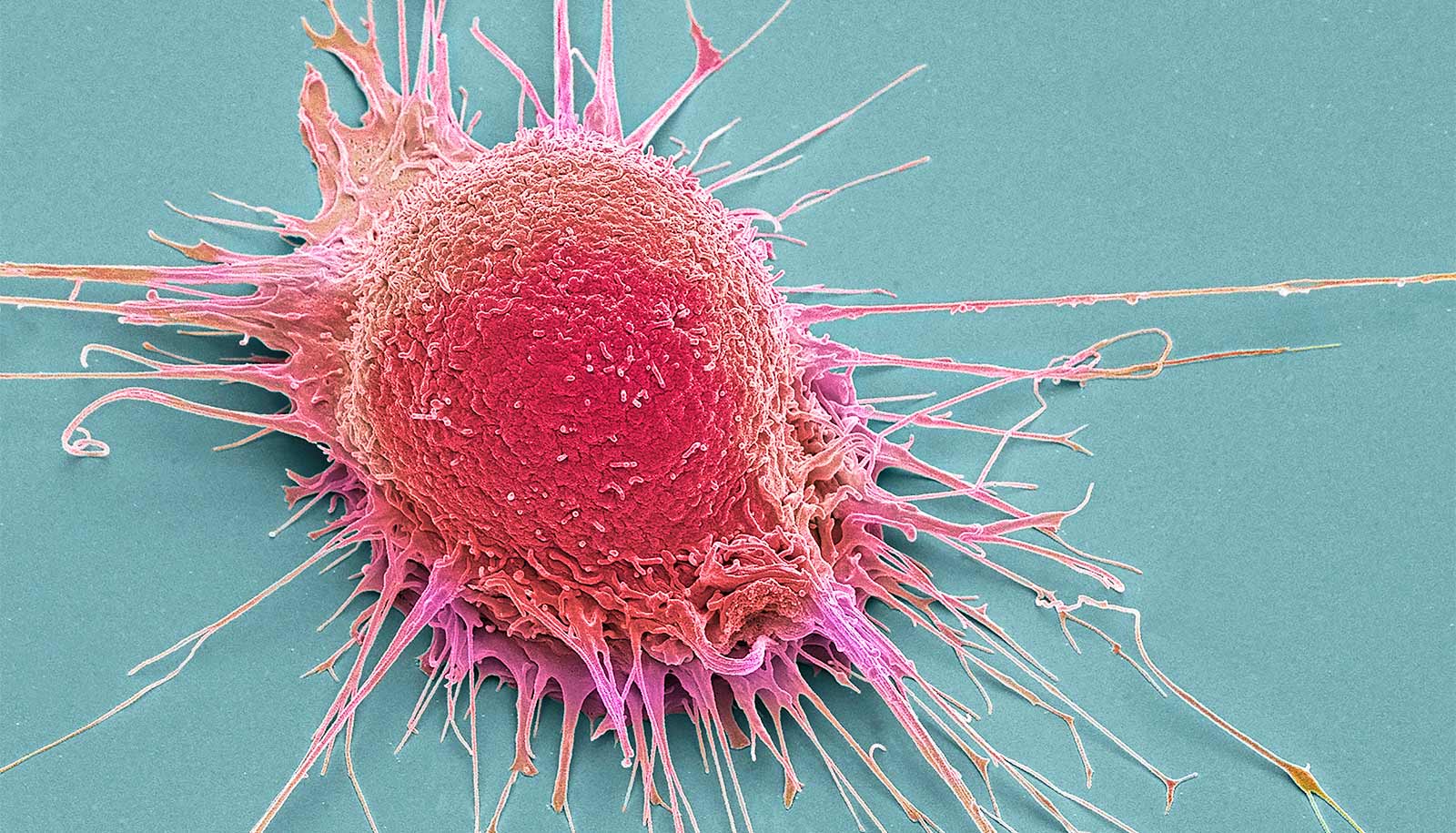

Unfortunately, during recovery, any remaining cancer cells will continue to grow. To make matters more complicated, remaining cancer cells, mainly cancer stem cells, can be more resistant to radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

The new approach adds chemotherapy prior to radiotherapy—a process called neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. Giving neo-adjuvant chemotherapy prevented the tumor from progressing during recovery and increased survival. After the neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, patients then received accelerated radiotherapy.

“We had better control over the tumor by giving patients the same overall dose of radiotherapy in fewer sessions and a shorter period of time. By doing this, we increased the efficacy of the treatment and we believe that in turn the treatment targeted the stem cells, which are the basis of recurrence,” Shenouda says.

“Reducing the radiotherapy sessions by one-third also alleviates the burden for patients. In addition, this represents a considerable cost reduction of delivery of treatment.”

Although additional research is required, the initial results are very promising, Shenouda says. “Fifty percent of the patients in our study have survived two years since their diagnosis—this is very encouraging and we are very positive about the outcome.”

Source: McGill University