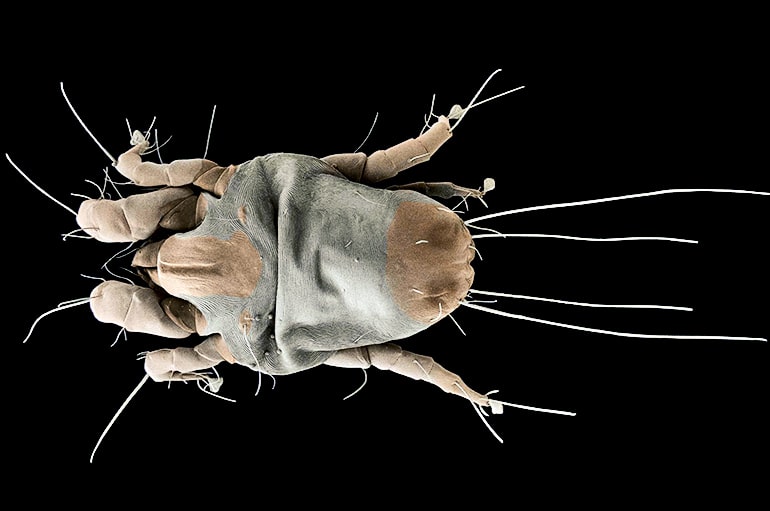

As a consequence of their tumultuous evolutionary history, the house dust mite developed a novel way to protect its genome from internal disruptions, a new genetic study suggests.

House dust mites are ubiquitous inhabitants of human dwellings, thriving in the mattresses, sofas, and carpets of even the cleanest homes. They are the primary cause of indoor allergies in humans, affecting up to 1.2 billion people worldwide.

All animals and plants face a threat from transposable elements, pieces of non-coding DNA that can change their position in the genome, often causing mutations and disease, but have evolved complex ways to watch for, target, and silence the threat.

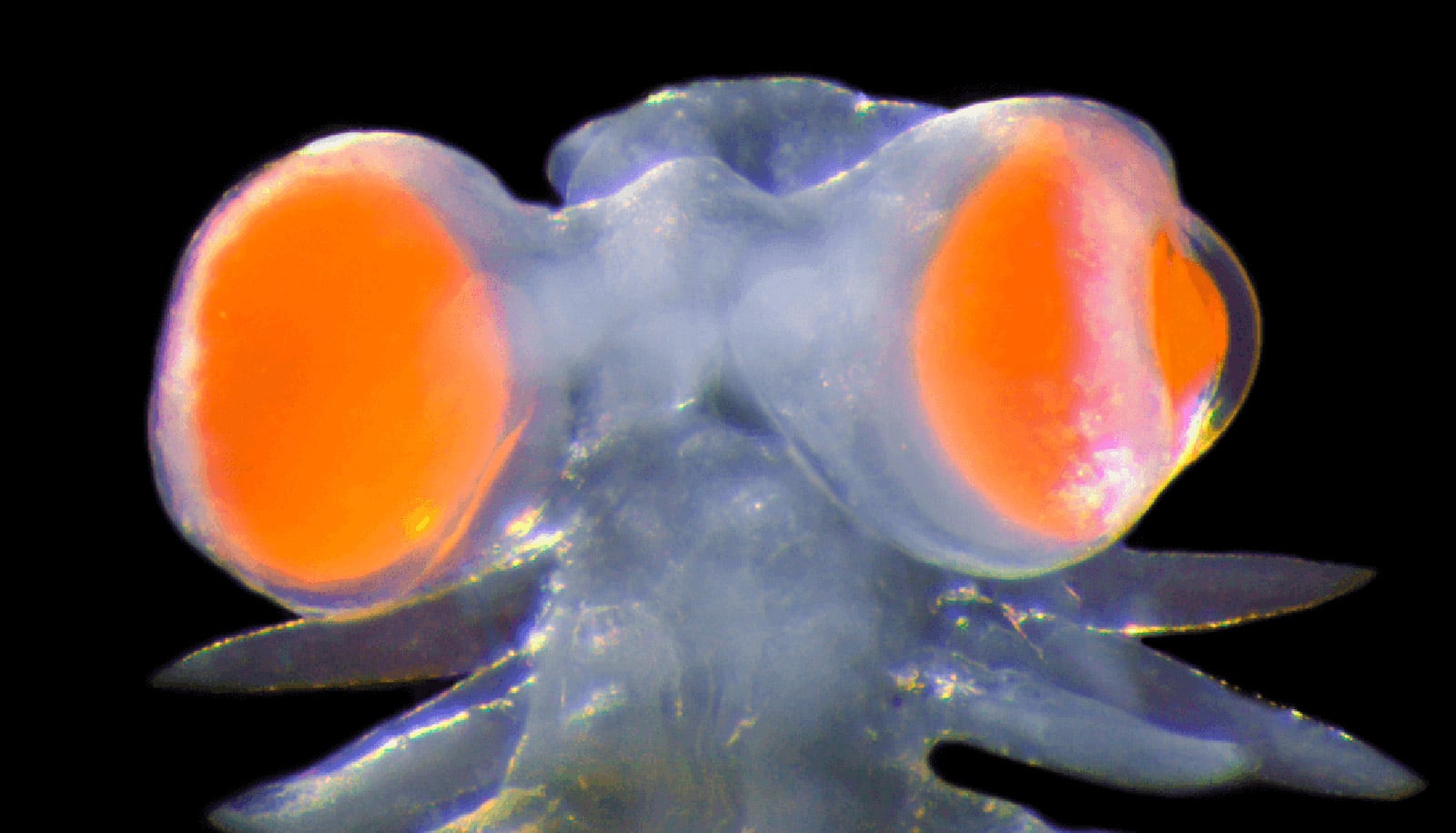

In most animals, this surveillance mission is carried out by small RNA fragments that find and break offending genetic sequences. The mechanism is called the piwi-associated RNA pathway—named for the protein Piwi, first discovered in fruit flies.

Researchers sequenced the DNA and the RNA of the American house dust mite, Dermatophagoides farina. Then they looked at the populations of small RNA molecules encoded there.

The researchers found that house dust mites don’t have Piwi proteins or the associated small RNAs that most animals use to control transposable elements.

Instead, dust mites have replaced the Piwi pathway with a completely different small RNA mechanism that uses small-interfering RNAs. The dust mite genome also encodes a protein that can amplify small-interfering RNAs.

Vaccine triggers alarm to fight dust mite allergy

“We believe that the evolution of this novel mechanism to protect genomes from transposable elements is linked to the unusual evolution of the dust mite,” says Pavel Klimov, an associate research scientist in the ecology and evolutionary biology department at the University of Michigan and a coauthor of the paper that appears in PLOS Genetics.

“These animals evolved from parasitic ancestors. Frequently, the transition to parasitism is associated with dramatic genetic changes, a legacy carried by the dust mite when it moved back to a free-living lifestyle.”

Today’s tiny, free-living animals evolved from a parasitic ancestor 48 to 68 million years ago, which itself evolved from free-living organisms millions of years ago. Ancient dust mites lived in bird nests for millions of years before moving into human dwellings relatively recently.

Scientists from the University of Southern Mississippi led the research. The National Science Foundation and the Mississippi INBRE program, which is funded by the National Institutes of General Medical Sciences supported the work.

Source: University of Michigan