Researchers have developed three new methods to detect cyberattacks on 3D printers.

“They will be attractive targets because 3D-printed objects and parts are used in critical infrastructures around the world, and cyberattacks may cause failures in health care, transportation, robotics, aviation, and space,” says Saman Aliari Zonouz, an associate professor in the electrical and computer engineering department at Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

Zonouz coauthored the study describing the methods for protecting 3D printers from hackers, which was published at the 26th USENIX Security Symposium in Vancouver, Canada.

“Imagine outsourcing the manufacturing of an object to a 3D printing facility and you have no access to their printers and no way of verifying whether small defects, invisible to the naked eye, have been inserted into your object,” says Mehdi Javanmard, study coauthor and assistant professor in the electrical and computer engineering department at the university.

“The results could be devastating and you would have no way of tracing where the problem came from,” he says.

“You’ll see more types of attacks as well as proposed defenses in the 3D printing industry within about five years…”

3D printing, also called additive manufacturing, plays an increasingly important role in industrial manufacturing. But health- and safety-related products such as medical prostheses and aerospace and auto parts are being printed with no standard way to verify them for accuracy, the study says. Even houses and buildings are being manufactured by 3D printers, notes Javanmard.

Proving hacks are possible

Instead of spending up to $100,000 or more to buy a 3D printer, many companies and organizations send software-designed products to outside facilities for printing, Zonouz says. But the firmware in printers may be hacked.

For their study, the researchers bought several 3D printers and showed that it’s possible to hack into a computer’s firmware and print defective objects. The defects were undetectable on the outside but the objects had holes or fractures inside them.

Other researchers have shown in a YouTube video how hacking can lead to a defective propeller in a drone, causing it to crash, Zonouz notes.

While anti-hacking software is essential, it’s never 100 percent safe against cyberattacks. So the researchers looked at the physical aspects of 3D printers.

3D printing helps predict if new heart valves will leak

3 ways to keep 3D printing secure

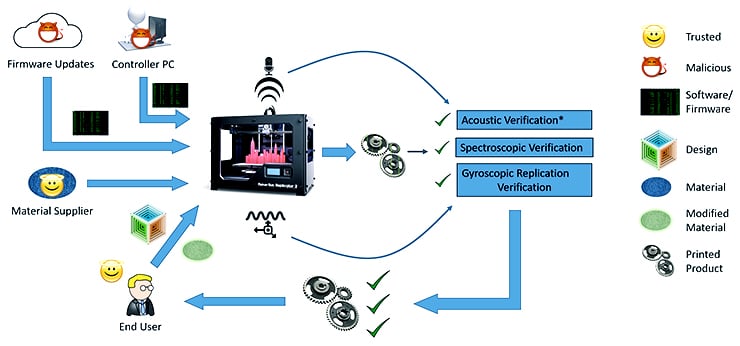

The three methods researchers have developed to detect hacking attacks on 3D printers include:

- Acoustic measurement of the 3D printer in operation. When compared to a reference recording of a correct print, this acoustic monitoring—done with an inexpensive microphone and filtering software—can detect changes in the printer’s sound that may indicate installation of malicious software.

- Physical tracking of printer components. To create the desired object, the printer’s extruder and other components should follow a consistent mechanical path that can be observed with inexpensive sensors. Variations from the expected path could indicate an attack.

- Detection of nanorods in finished components. Using Raman Spectroscopy and computed tomography (CT), the researchers were able to detect the location of gold nanorods that had been mixed with the filament material used in the 3D printer. Variations from the expected location of those particles could indicate a quality problem with the component. The variations could result from malicious activity, or from efforts to conserve printer materials.

In 3D printing, the software controls the printer, which fulfills the virtual design of an object. The physical part includes an extruder or “arm” through which filament (plastic, metal wire, or other material) is pushed to form an object.

The researchers observed the motion of the extruder, using sensors, and monitored sounds made by the printer via microphones.

“Just looking at the noise and the extruder’s motion, we can figure out if the print process is following the design or a malicious defect is being introduced,” Zonouz says.

The third method they developed involves examining an object to see if it was printed correctly. Tiny gold nanoparticles, acting as contrast agents, are injected into the filament and sent with the 3D print design to the printing facility. Once the object is printed and shipped back, high-tech scanning reveals whether the nanoparticles—a few microns in diameter—have shifted in the object or have holes or other defects.

“This idea is kind of similar to the way contrast agents or dyes are used for more accurate imaging of tumors as we see in MRIs or CT scans,” Javanmard says.

The next steps in their research include investigating other possible ways to attack 3D printers, proposing defenses, and transferring methods to industry, Zonouz says.

Among the challenges ahead will be obtaining good acoustic data in the noisy environments in which 3D printers typically operate. In the research, operation of other 3D printers near the one being observed cut the accuracy significantly, but Raheem Beyah, a professor and associate chair in Georgia Tech’s School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, believes that challenge can be addressed with additional signal processing.

“These 3D printed components will be going into people, aircraft, and critical infrastructure systems,” says Beyah. “Malicious software installed in the printer or control computer could compromise the production process. We need to make sure that these components are produced to specification and not affected by malicious actors or unscrupulous producers.”

Ink designed to 3D print bone implants for kids

“You’ll see more types of attacks as well as proposed defenses in the 3D printing industry within about five years,” Zonouz says.

Additional coauthors of this study are from the Georgia Institute of Technology and Rutgers University.

Source: Rutgers University, Georgia Tech