A controversial drug may offer a way to reduce the mucus shield that coats cancer cells and allows them to multiply and spread.

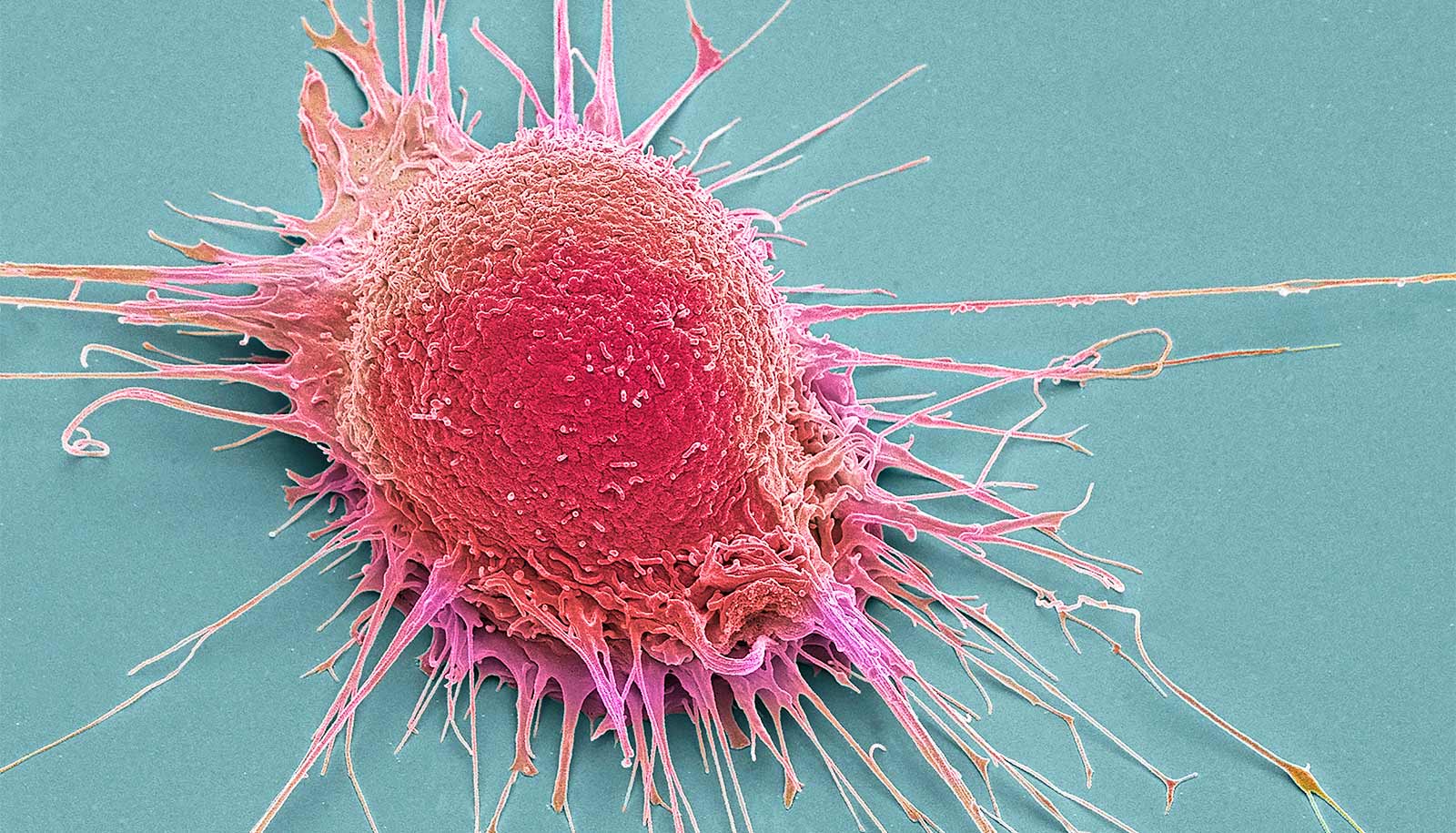

Researchers found that protein receptors on the surface of cancer cells go into overdrive to stimulate the production of MUC1, a glycoprotein that forms mucin, or mucus. It covers the exposed tips of the elongated epithelial cells that coat internal organs like lungs, stomach, and intestines to protect them from infection.

But when associated with cancer cells, these slippery agents do their jobs too well. They cover the cells completely, help them metastasize, and protect them from attack by chemotherapy and the immune system. The research is published in the Journal of Cellular Biochemistry.

[related]

In the paper, biochemist Daniel Carson, dean of Rice University’s Wiess School of Natural Sciences, lead author Neeraja Dharmaraj, a postdoctoral researcher, and graduate student Brian Engel describe EGFR as a powerful transmembrane protein that stimulates normal cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation. “What hadn’t been considered is whether this activated receptor might actually promote the expression of MUC1, which would then further elevate the levels of EGFR and create this vicious cycle,” Carson says.

“That’s the question we asked, and the answer is ‘yes’,” he says.

Carson compared mucus to Teflon. “Things don’t stick to it easily, which is normally what you want. It’s a primary barrier that keeps nasty stuff like pathogenic bacteria and viruses from getting into your cells,” he says.

But cancer cells “subvert systems and find ways to get out of control,” he says. “They auto-activate EGFR by making their own growth factor ligands, for example, or mutating the receptor so it doesn’t require the ligand anymore. It’s always on.”

Mucin proteins can then cover entire surface of a cell. “That lets (the cell) detach and move away from the site of a primary tumor,” while still preventing contact with immune system cells and cytotoxins that could otherwise kill cancer cells, Carson says.

Hope comes in the form of a controversial drug, rosiglitazone, in the thiazolidinedione class of medications used in diabetes treatment, he says. The drug is suspected of causing heart problems over long-term use by diabetes patients. But tests on cancer cell lines found that it effectively attenuates the activation of EGFR and reduces MUC1 expression. That could provide a way to weaken the mucus shield.

“Chronic use of rosiglitazone can produce heart problems in a subset of patients, but if you’re dying of pancreatic cancer, you’re not worried about the long term,” Carson says. “If you can reduce mucin levels in just a few days by using these drugs, they might make cancer cells easier to kill by established methods.”

He says more work is required to see if rosiglitazone or some variant is suitable for trials. “We think it’s best to understand all the effects,” he says. “That might give us a rational way to modify these compounds, to avoid unwanted side effects and focus on what we want them to do.”

The National Institutes of Health and Rice University supported the research.

Source: Rice University