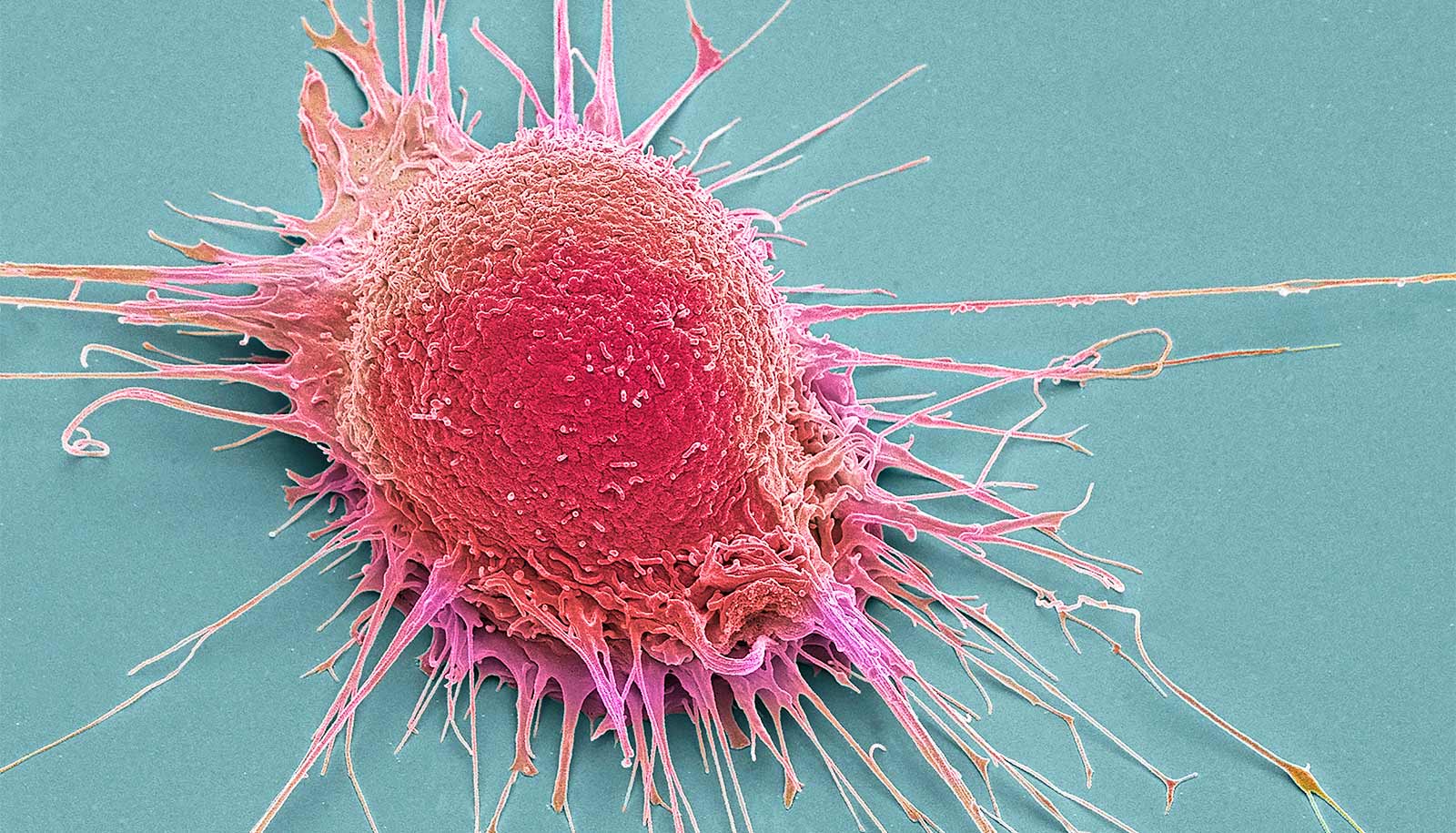

Recent research demonstrated that mature cells in the stomach sometimes revert back to behaving like rapidly dividing stem cells. Now, the researchers have found that this process may be universal, no matter the organ.

The research, which appears in the EMBO Journal, indicates that when tissue responds to certain types of injury, mature cells seem to get younger and begin dividing rapidly, creating scenarios that can lead to cancer.

Hear senior investigator Jason C. Mills discuss the findings:

Older cells may be dangerous because when they revert to stem cell-like behavior, they carry with them all of the potential cancer-causing mutations that have accumulated during their lifespans. However, because mature cells in the stomach, pancreas, liver, and kidney all activate the same genes and go through the same process when they begin to divide again, the findings could mean that cancer initiation is much more similar across organs than scientists have thought. That could support using the same strategies to treat or prevent cancer in a variety of different organs.

“When we began the war on cancer in the 1970s, scientists thought all cancers were similar,” says senior investigator Jason C. Mills, a professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

“It turned out cancers are very different from one organ to another and from person to person. But if, as this study suggests, the way that cells become proliferative again is similar across many different organs, we can imagine therapies that interfere with cancer initiation in a more global way, regardless of where that cancer may appear in the body,” he explains.

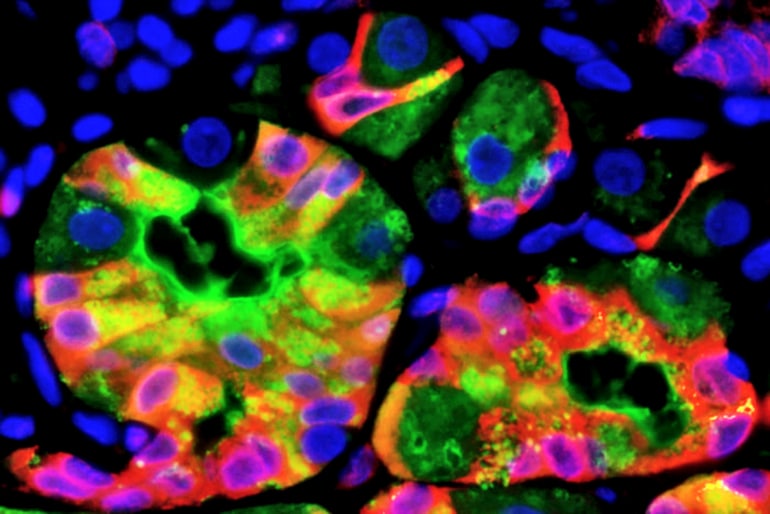

Studying cells from the stomach and pancreas in humans and mice, as well as mouse kidney and liver cells, and cells from more than 800 tumor and precancerous lesions in people, the researchers found when tissue is injured by infections or trauma, mature cells can revert back to a stem-cell state in which they divide repeatedly. And along the way, those cells all activate the same genes to break down the mature cells and help them begin to divide again.

“First, we saw a massive increase in the activity of genes associated with cell degradation,” says first author Spencer G. Willet, a research associate in the Mills lab. “Then, the cell’s growth pathway senses that degradation and releases nutrients that then activate cell growth pathways and allow the mature cells we studied to proliferate.”

Mature cells can act like stem cells to kickstart cancer

Paligenosis, Mills explains, appears similar to apoptosis—the programmed death of cells as a normal part of an organism’s growth and development—in that it seems to happen the same way in every cell, regardless of its location in the body.

“Nature has provided a way for mature cells to begin dividing again,” Mills says, “and that process is the same in every tissue we’ve studied.”

Willet, Mills, and their colleagues believe the discovery that cells in different organs go through the same process to become proliferative could lead to new potential targets for cancer treatment because the factors that initiate tumors could be the same in multiple organs.

“If you were to compare this reprogramming of cells to tearing down a building and putting something new in its place, the slow way to go would be to remove and then replace each brick, one at a time,” Mills says. “What we’re seeing is that nature is smarter than just running the building program in reverse. Instead, there is a wrecking ball program: When an old cell begins to divide again, a program runs to clear things out and then rebuild, and the same program runs in every tissue we’ve analyzed.”

These proteins keep stem cells ‘immature’

The funding for the work came from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; the National Institute of General Medical Sciences; the National Cancer Institute; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Additional funding came from the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center/Barnes Jewish Hospital Foundation Cancer Frontier Fund, the Barnard Trust, the DeNardo Education & Research Foundation, the Philip and Sima Needleman Student Fellowship in Regenerative Medicine, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.