“Nanosponges” appear to stop the coronavirus infection in its tracks by diverting its attention away from living lung cells, researchers report.

The technology could have major implications for fighting the SARS-CoV-2 virus responsible for the global pandemic that’s already claimed nearly 450,000 lives and infected more than 8 million people. But, perhaps even more significantly, it has the potential to be adapted to combat virtually any virus, such as influenza or even Ebola.

“Conceptually, it’s such a simple idea. It mops up the virus like a sponge.”

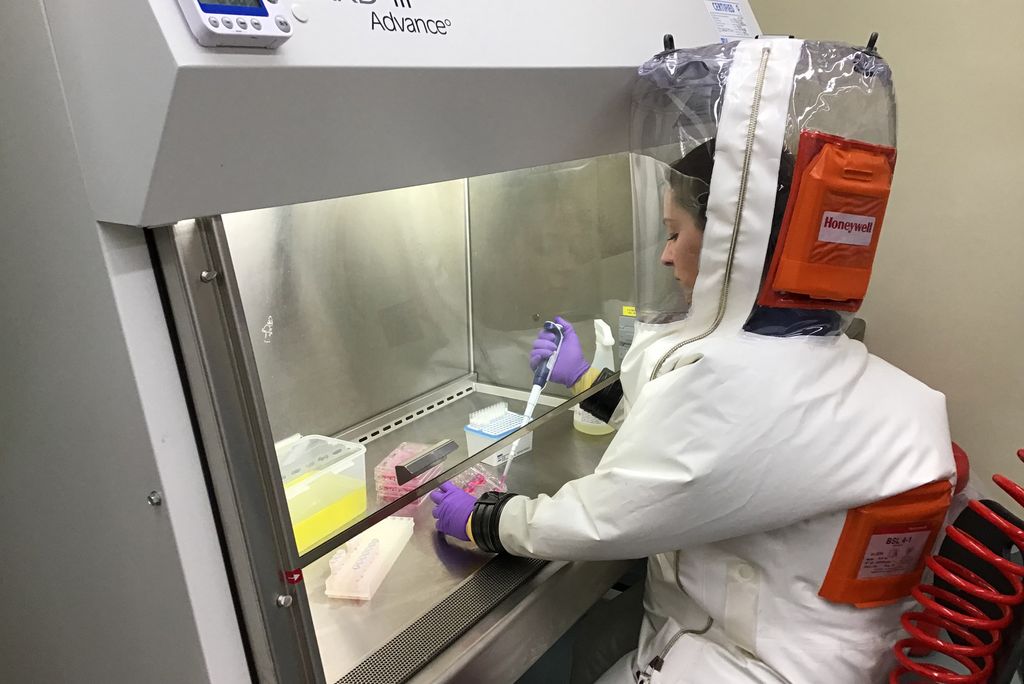

“I was skeptical at the beginning because it seemed too good to be true,” says co-first author Anna Honko, a microbiologist at Boston University’s National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL). “But when I saw the first set of results in the lab, I was just astonished.”

The technology consists of very small, nanosized drops of polymers—essentially, soft biofriendly plastics—covered in fragments of living lung cell and immune cell membranes.

“It looks like a nanoparticle coated in pieces of cell membrane,” Honko says. “The small polymer [droplet] mimics a cell having a membrane around it.”

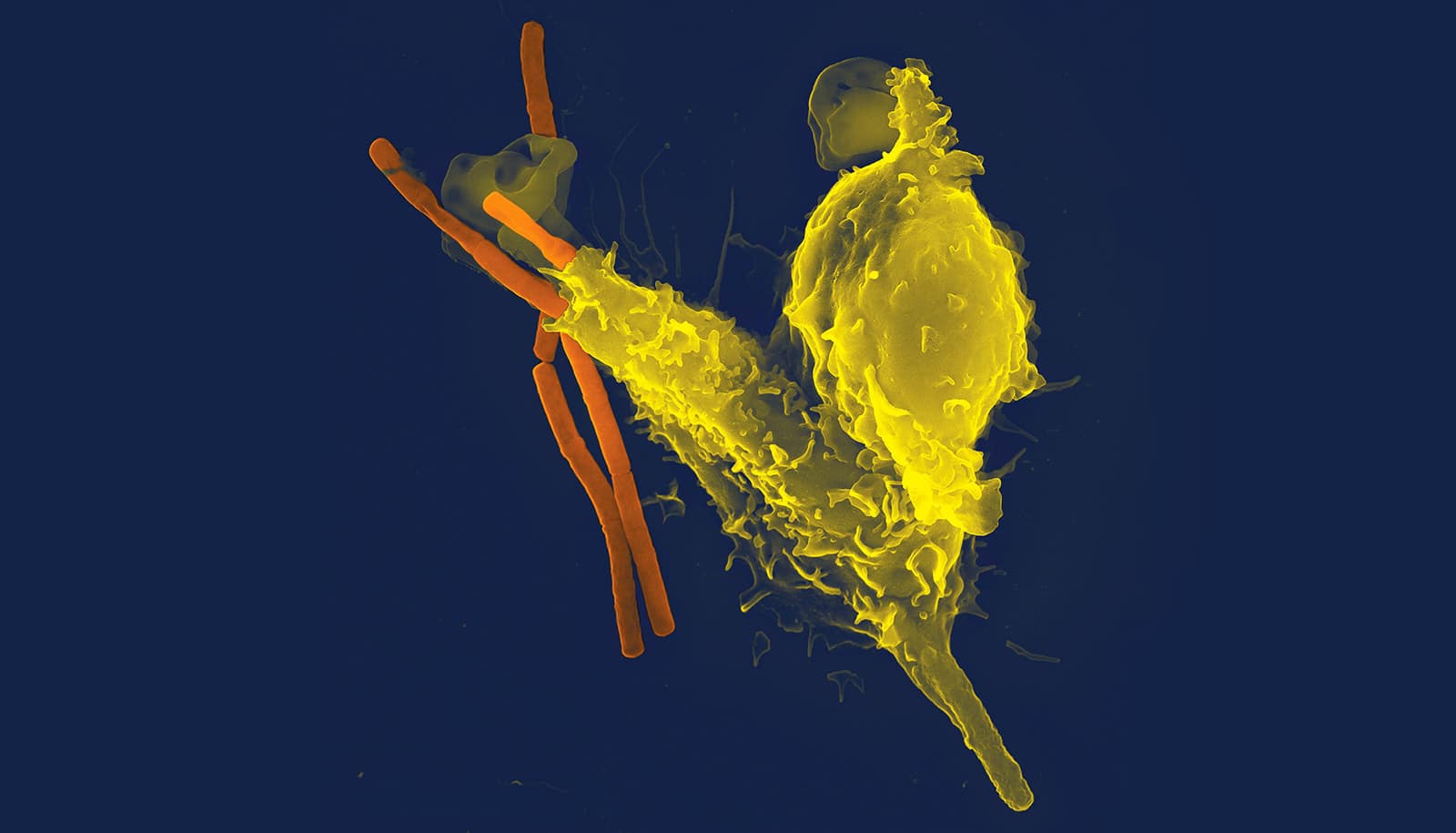

The SARS-CoV-2 virus seeks out unique signatures of lung cell membranes and latches onto them. When that happens inside the human body, the coronavirus infection takes hold, with the SARS-CoV-2 viruses hijacking lung cells to replicate their own genetic material. But in new experiments, researchers observed that polymer droplets laden with pieces of lung cell membrane did a better job of attracting the SARS-CoV-2 virus than living lung cells.

By fusing with the SARS-CoV-2 virus better than living cells can, the nanotechnology appears to be an effective countermeasure to coronavirus infection, preventing SARS-CoV-2 from attacking cells.

“Our guess is that it acts like a decoy, it competes with cells for the virus,” says co-corresponding author Anthony Griffiths, also a NEIDL microbiologist. “They are little bits of plastic, just containing the outer pieces of cells with none of the internal cellular machinery contained inside living cells. Conceptually, it’s such a simple idea. It mops up the virus like a sponge.”

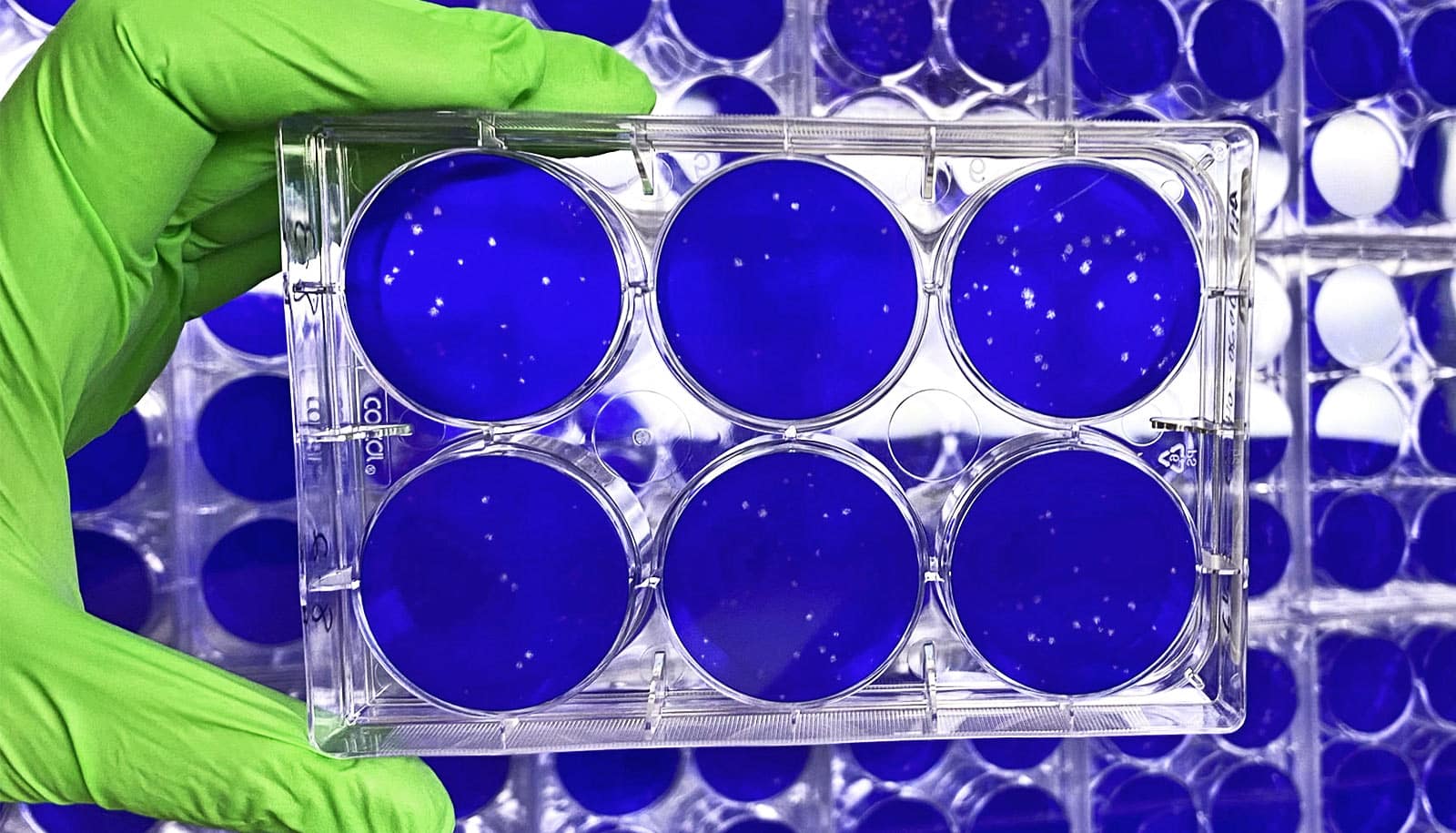

That attribute is why the researchers call the technology “nanosponges.” Once SARS-CoV-2 binds with the cell fragments inside a nanosponge droplet—each one a thousand times smaller than the width of a human hair—the coronavirus dies. Although the initial results are based on experiments conducted in cell culture dishes, the researchers believe that inside a human body, the biodegradable nanosponges and the SARS-CoV-2 virus trapped inside them could then be disposed of by the body’s immune system. The immune system routinely breaks down and gets rid of dead cell fragments caused by infection or normal cell life cycles.

There is also another important effect that the nanosponges have in the context of coronavirus infection. Honko says nanosponges containing fragments of immune cells can soak up cellular signals that increase inflammation. Acute respiratory distress, caused by an inflammatory cascade inside the lungs, is the most deadly aspect of the coronavirus infection, sending patients into the intensive care unit for oxygen or ventilator support to help them breathe.

But the nanosponges, which can attract the inflammatory molecules that send the immune system into dangerous overdrive, can help tamp down that response, Honko says. By using both kinds of nanosponges, some containing lung cell fragments and some containing pieces of immune cells, she says it’s possible to “attack the coronavirus and the [body’s] response” responsible for disease and eventual lung failure.

“We should be able to drop it right into the nose. In humans, it could be something like a nasal spray.”

At the NEIDL, Honko and Griffiths are now planning additional experiments to see how well the nanosponges can prevent coronavirus infection in animal models of the disease. They plan to work closely with the team of engineers at UC San Diego, who first developed the nanosponges more than a decade ago, to tailor the technology for eventual safe and effective use in humans.

“Traditionally, drug developers for infectious diseases dive deep on the details of the pathogen in order to find druggable targets,” says Liangfang Zhang, a nanoengineer at the University of California, San Diego. “Our approach is different. We only need to know what the target cells are. And then we aim to protect the targets by creating biomimetic decoys.”

When the novel coronavirus first appeared, the idea of using the nanosponges to combat the infection came to Zhang almost immediately. He reached out to the NEIDL for help. Looking ahead, the researchers believe the nanosponges can easily be converted into a noninvasive treatment.

“We should be able to drop it right into the nose,” Griffiths says. “In humans, it could be something like a nasal spray.”

Honko agrees: “That would be an easy and safe administration method that should target the appropriate [respiratory] tissues. And if you wanted to treat patients that are already intubated, you could deliver it straight into the lung.”

Griffiths and Honko are especially intrigued by the nanosponges as a new platform for treating all types of viral infections.

“The broad spectrum aspect of this is exceptionally appealing,” Griffiths says.

The researchers say the nanosponge could be easily adapted to house other types of cell membranes preferred by other viruses, creating many new opportunities to use the technology against other tough-to-treat infections like the flu and even deadly hemorrhagic fevers caused by Ebola, Marburg, or Lassa viruses.

“I’m interested in seeing how far we can push this technology,” Honko says.

The research appears in a Nano Letters. The Defense Threat Reduction Agency Joint Science and Technology Office for Chemical and Biological Defense supported the research.

Source: Boston University