The mammoth pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus probably jumped at least 8 feet into the air before lifting off by sweeping its wings, according to new research.

With a wingspan nearing 40 feet, Quetzalcoatlus is the largest known animal to take to the sky. But just how such a massive animal got airborne has been mostly a matter of speculation.

Some think it rocked forward on its wingtips like a vampire bat. Or that it built up speed by running and flapping like an albatross. Or that it didn’t fly at all.

The new research may end the debate.

The finding is part of the most comprehensive study of the pterosaur yet, and one of many to come from a new collection of Quetzalcoatlus research in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

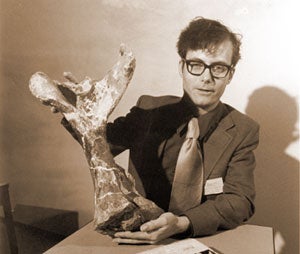

Seen in movies, comic strips, and suspended from museum ceilings, the giant “Texas Pterosaur” has been a media staple since it was discovered in 1971 by Douglas Lawson, then a 22-year-old geology graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin, in Big Bend National Park.

However, science has not kept up with the pterosaur’s popular image. Aside from Lawson’s early descriptions of the fossils, almost no scientific research has been published based on direct study of the bones.

This new research collection—a monograph made up of an introduction and five studies—helps remedy that, says Matthew Brown, co-editor of the collection and director of the University of Texas at Austin’s Vertebrate Paleontology Collections at the Jackson School of Geosciences.

“This is the first time that we have had any kind of comprehensive study,” Brown says. “Even though Quetzalcoatlus has been known for 50 years, it has been poorly known.”

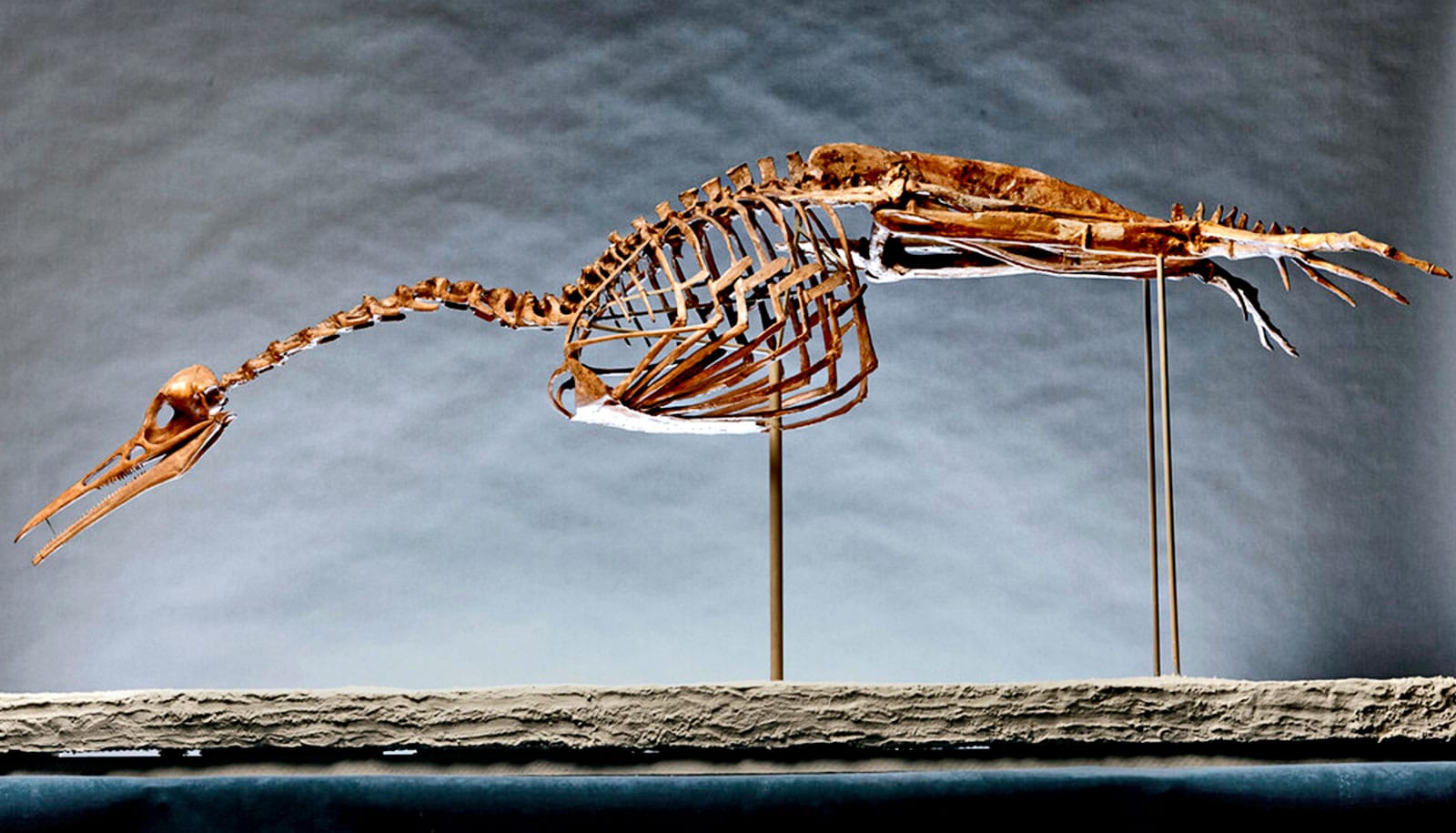

The University of Texas collections hold all known Quetzalcoatlus fossils. The new research involved close study of all confirmed and suspected Quetzalcoatlus bones, along with other pterosaur fossils recovered from Big Bend. This led to the identification of two new pterosaur species—including a new, smaller species of Quetzalcoatlus with an 18-to-20-foot wingspan.

Brian Andres, who began studying Quetzalcoatlus as an undergraduate at the Jackson School and is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Sheffield, performed the analysis and named the new species Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni in honor of Lawson.

Whereas the larger species, Quetzalcoatlus northropi, is known from only about a dozen bones, there are hundreds of fossils from the smaller species. This provided enough material for scientists to reconstruct a nearly complete skeleton of the smaller species and study how it flew and moved. They then applied their insights to its larger cousin.

Kevin Padian, an emeritus professor and emeritus curator at the University of California, Berkeley, and co-editor of the research collection, led the biomechanics research.

“Pterosaurs have huge breastbones, which is where the flight muscles attach, so there is no doubt that they were terrific flyers,” he says.

The two Quetzalcoatlus species both called Big Bend home about 70 million years ago, when the region was an evergreen forest instead of the desert of today. But each led a distinct lifestyle, according to Thomas Lehman, who started his research as a doctoral student at the Jackson School and is now a professor at Texas Tech University.

By examining the geological context in which the fossils were found, Lehman determined that the larger Quetzalcoatlus might have lived like today’s herons, hunting alone in rivers and streams. The smaller species, in contrast, appeared to flock together in lakes—either year-round or seasonally to mate—with at least 30 individuals found at a single fossil site.

Over the years, researchers and artists have pictured Quetzalcoatlus as a skimmer, forager, and scavenger. In his study, Lehman presents Quetzalcoatlus as a prober that used its long, toothless jaws to sift for crabs, worms, and clams from river bottoms and lakebeds.

Wann Langston, Jr. the former director of the University of Texas Vertebrate Paleontology Collections, spent decades studying Quetzalcoatlus. But he was unable to publish most of his findings before he died in 2013. To acknowledge his contributions, Langston is listed as a coauthor of two of the studies.

The science presented in the monograph is a boon to pterosaur science and will serve as a springboard for future research, says Darren Naish, a paleozoologist and pterosaur expert who was not involved with the research.

“To say that this work is long awaited is something of an understatement. The good news is that it very much delivers, providing the definite treatment of this iconic animal.”

“Never before has so much detailed information on azhdarchids (the pterosaur family that includes Quetzalcoatlus) been gathered in the same place, this meaning that the work will serve as the standard go-to study of this group for years—probably decades—to come.”

Source: University of Texas at Austin