New research identifies a gene that likely plays a causal role in coronary artery disease, independent of cholesterol levels.

The gene also likely has roles in related cardiovascular diseases, including high blood pressure and diabetes.

The new findings appear in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

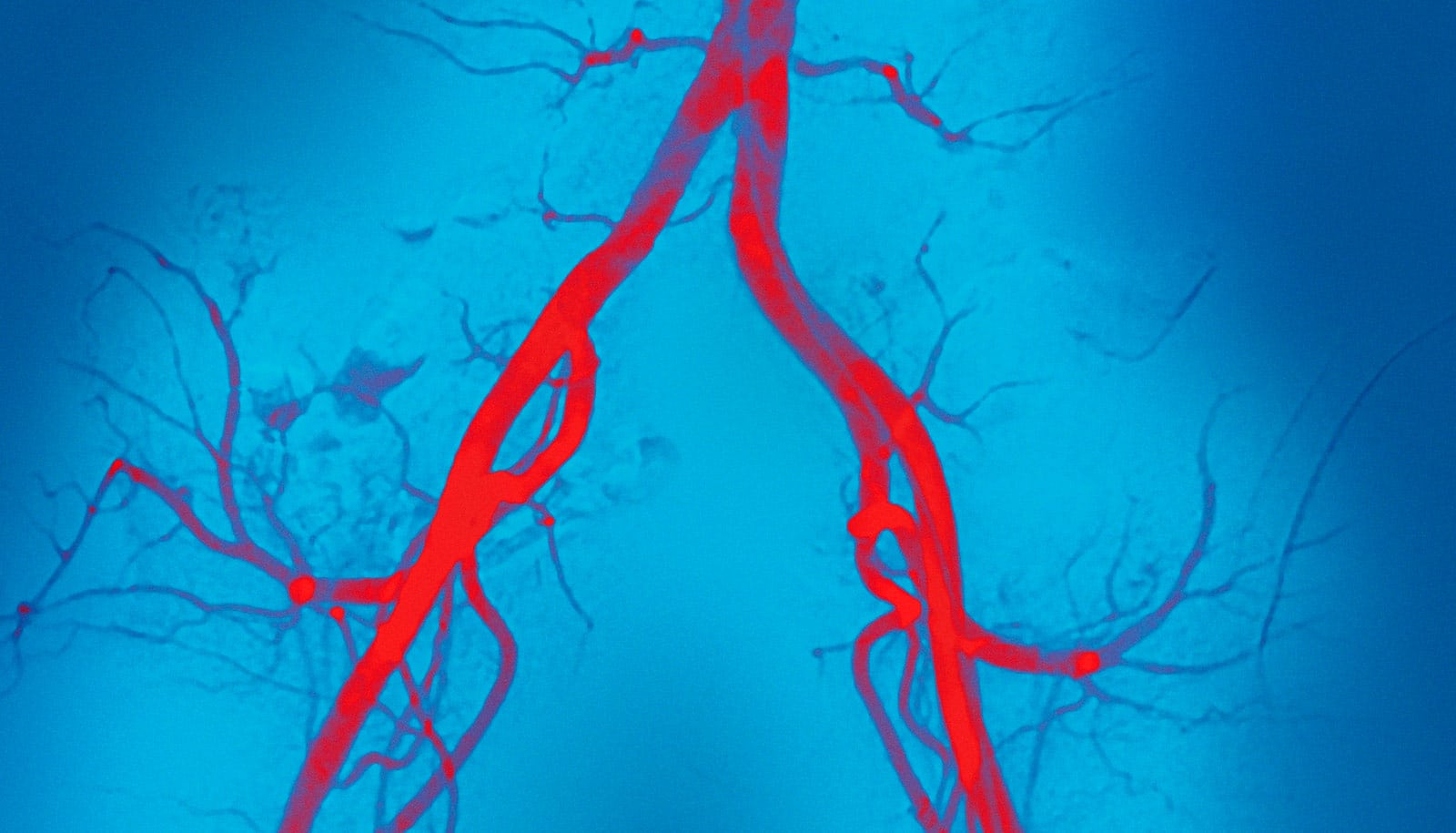

Studying mice and genetic data from people, the researchers found that the gene—called SVEP1—makes a protein that drives the development of plaque in the arteries. In mice, animals missing one copy of SVEP1 had less plaque in the arteries than mice with both copies. The researchers also selectively reduced the protein in the arterial walls of mice, and this further reduced the risk of atherosclerosis.

Evaluating human genetic data, the researchers found that genetic variation influencing the levels of this protein in the body correlated with the risk of developing plaque in the arteries. Genetically determined high levels of the protein meant higher risk of plaque development and vice versa. Similarly, they found higher levels of the protein correlated with higher risk of diabetes and higher blood pressure readings.

“Cardiovascular disease remains the most common cause of death worldwide,” says cardiologist Nathan O. Stitziel, associate professor of medicine and of genetics at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

“A major goal of treatment for cardiovascular disease has appropriately been focused on lowering cholesterol levels. But there must be causes of cardiovascular disease that are not related to cholesterol—or lipids—in the blood. We can decrease cholesterol to very low levels, and some people still harbor residual risk of future coronary artery disease events. We’re trying to understand what else is going on, so we can improve that as well.”

This is not the first nonlipid gene identified that has been implicated in cardiovascular disease. But the exciting aspect of this discovery is that it lends itself better to developing future therapies, according to the investigators.

The researchers—including co-first authors In-Hyuk Jung, a staff scientist, and Jared S. Elenbaas, a doctoral student in Stitziel’s lab—further show that this protein is a complex structural molecule and is manufactured by vascular smooth muscle cells, which are cells in the walls of blood vessels that contract and relax the vasculature.

The protein was shown to drive inflammation in the plaques in the artery walls and to make the plaques less stable. Unstable plaque is particularly dangerous because it can break loose, leading to the formation of a blood clot, which can cause heart attack or stroke.

“In animal models, we found that the protein induced atherosclerosis and promoted unstable plaque,” Jung says. “We also saw that it increased the number of inflammatory immune cells in the plaque and decreased collagen, which serves a stabilizing function in plaques.”

According to Stitziel, other genes previously identified as raising the risk of cardiovascular disease independent of cholesterol appear to have widespread roles in the body and are therefore more likely to have far-reaching undesirable side effects if blocked in an effort to prevent cardiovascular disease. Although SVEP1 is required for early development of the embryo, eliminating the protein in adult mice did not appear to be detrimental, according to the researchers.

“The human genetic data showed a naturally occurring wide range of this protein in the general population, suggesting that we might be able to alter its levels in a safe way and potentially decrease coronary artery disease,” Elenbaas says.

Ongoing work in Stitziel’s group is focused on seeking ways to block the protein or reduce its levels in an effort to identify new compounds or possible treatments for coronary artery disease and, perhaps, high blood pressure and diabetes. The researchers have worked with the university’s Office of Technology Management to file a patent for therapies that target the SVEP1 protein.

Support for the work came from the National Institutes of Health, the National Lipid Association, and The Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital.