The bright chirp of the coquí frog, the national symbol of Puerto Rico, has likely resounded through Caribbean forests for at least 29 million years, researchers report.

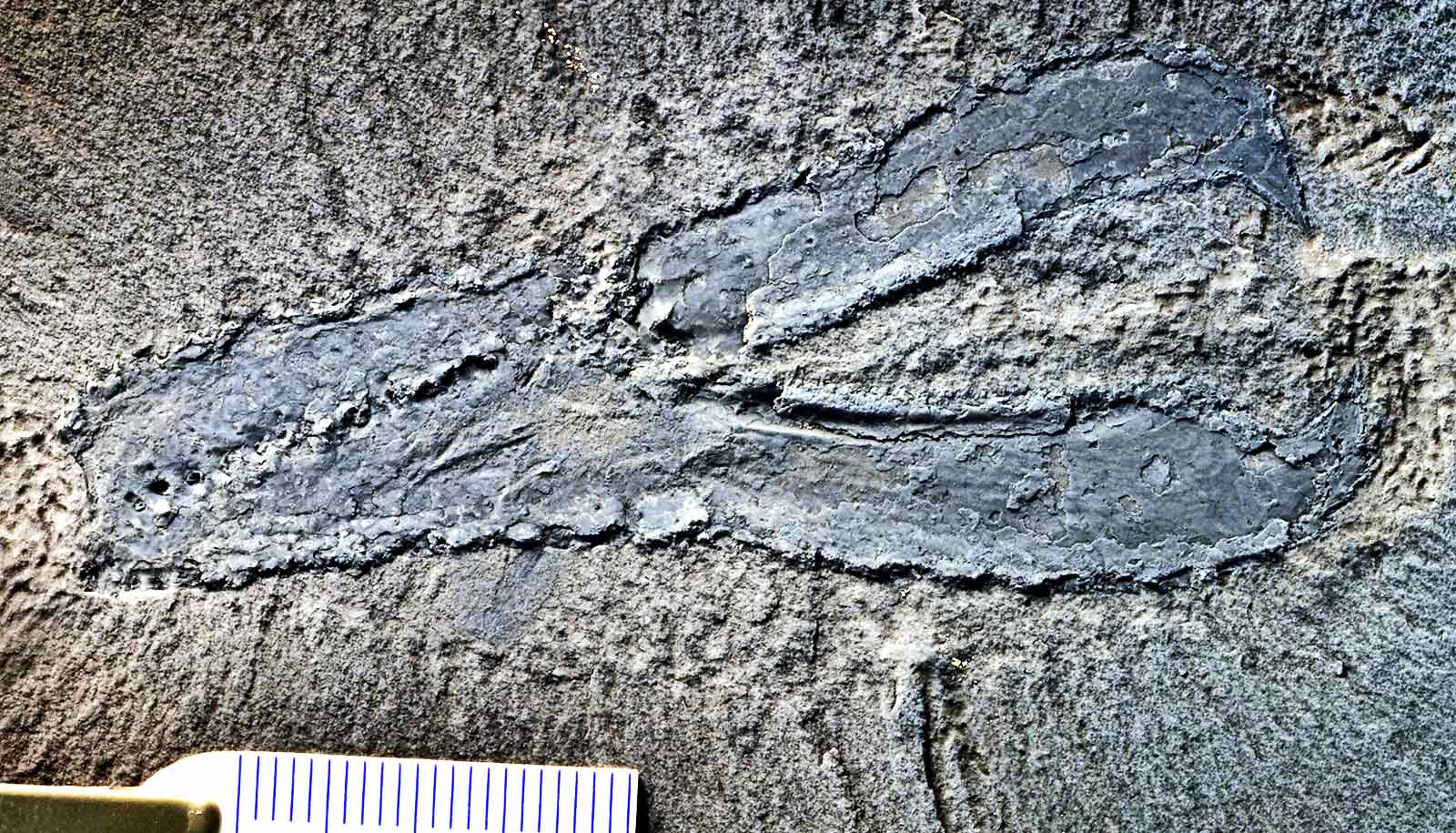

In a new study in Biology Letters, researchers describe a fragmented arm bone from a frog in the genus Eleutherodactylus, also known as rain frogs or coquís. They discovered the fossil, the oldest record of frogs in the Caribbean, on the island where coquís are most beloved.

“It’s a national treasure,” says lead author David Blackburn, curator of herpetology at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

“Not only is this the oldest evidence for a frog in the Caribbean, it also happens to be one of the frogs that are the pride of Puerto Rico and related to the large family Eleutherodactylidae, which includes Florida’s invasive greenhouse frogs.”

Coqui: Tiny bone, oldest frog

Jorge Velez-Juarbe, associate curator of marine mammals at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, found the fossil on a river outcrop in the municipality of San Sebastian in northwestern Puerto Rico.

Velez-Juarbe and his collaborators’ previous collecting efforts at the site uncovered fossil seeds, sea cows, side-necked turtles, and the oldest remains of gharials and rodents in the Caribbean, dating to the early Oligocene Epoch, about 29 million years ago.

Still, “there have been many visits from which I have come out empty-handed over the last 14 years,” he says. “I’ve always kept my expectations not too high for this series of outcrops.”

On this trip in 2012, he combed the deposits for half a day without much luck when a small bone, partially exposed in the sediment, caught his eye. He examined it with his hand lens.

“At the moment, I couldn’t wrap my mind as to what it was,” Velez-Juarbe says. “Then once I got back home, cleaned around it with a needle to see it better and checked some references, I knew I had found the oldest frog in the Caribbean.”

The ancient coquí displaces an amber frog fossil discovered in the Dominican Republic in 1987 for the title of oldest Caribbean frog.

Researchers originally estimated the amber fossil was 40 million years old, but now scientists date Dominican amber to about 20 million to 15 million years ago, Blackburn says.

Based on genetic data and family trees, scientists had hypothesized rain frogs lived in the Caribbean during the Oligocene, but lacked any fossil evidence. The small, lightweight bones of frogs often do not preserve well, especially when combined with the hot, humid climate of the tropics.

Matching a single bone fragment to a genus or species “is not always an easy process,” Velez-Juarbe says. It can also depend on finding the right expert. His quest for help identifying the fossil turned up empty until a 2017 visit to the Florida Museum where he was once a postdoctoral researcher.

“I got to talk with Dave about projects, and the rest is now history,” he says.

Raft arrival

Possibly first arriving in the Caribbean by rafting from South America, frogs in the genus Eleutherodactylus, which encompasses some 200 species, dominate the region today.

“This is the most diverse group by two orders of magnitude in the Caribbean,” Blackburn says. “They’ve diversified into all these different specialists with various forms and body sizes. Several invasive species also happen to be from this genus. All this raises the question of how they got to be this way.”

One partial arm bone may not tell the whole story of coquí evolution—but it’s a start.

“I am thrilled that, little by little, we are learning about the wildlife that lived in Puerto Rico 29-27 million years ago,” Velez-Juarbe says. “Finds like this help us unravel the origins of the animals we see in the Caribbean today.”

Additional coauthors are from the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Source: University of Florida