Scientists have used artificial intelligence to speed the discovery of critical biomarkers that can predict, at diagnosis, if patients with chronic myeloid leukemia will respond to conventional treatment.

With this early prognosis, these patients could receive a life-saving bone marrow transplant during the early stages of the disease.

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a type of blood cancer that develops when a genetic mutation results in the permanent switching-on of an enzyme called a tyrosine kinase. The mutation forms in a blood stem cell in the bone marrow, and causes the stem cell to change into an aggressive leukemic cell, which eventually takes over healthy blood production.

The conventional treatment for CML is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), which switches off the tyrosine kinase that was turned on as a result of the genetic mutation. However, not everyone responds similarly to these drugs.

At one end of the spectrum, some patients respond exceptionally well—to the point where their life expectancy would be considered normal. At the other end, some patients hardly respond at all, and their disease progresses to an aggressive state called blast crisis that is resistant to all forms of standard therapy.

Because the only treatment for blast crisis is a bone marrow transplant, which would be most effective when performed during the early stages of the disease, finding out if a patient is resistant to TKI therapy sooner could mean the difference between survival or an early death.

“Our work indicates that it will be possible to detect patients destined to undergo blast crisis when they first see their hematologist,” says Ong Sin Tiong, associate professor in the Duke-NUS’ Cancer & Stem Cell Biology (CSCB) Programme and senior author of the paper in the journal Blood.

“This may save lives since bone marrow transplants for these patients are most effective during the early stages of CML.”

“Based on these findings, we aim to develop simple clinical tests that can advise physicians on the optimal choice of treatment at the time of diagnosis,” says first author Vaidehi Krishnan, principal research scientist with the CSCB Programme.

“Single cell analysis coupled with the power of AI have provided a crystal ball for predicting drug response in leukemia,” says Shyam Prabhakar, associate director of spatial and single cell systems and senior group leader of systems biology and data analytics at A*STAR’s Genome Institute of Singapore.

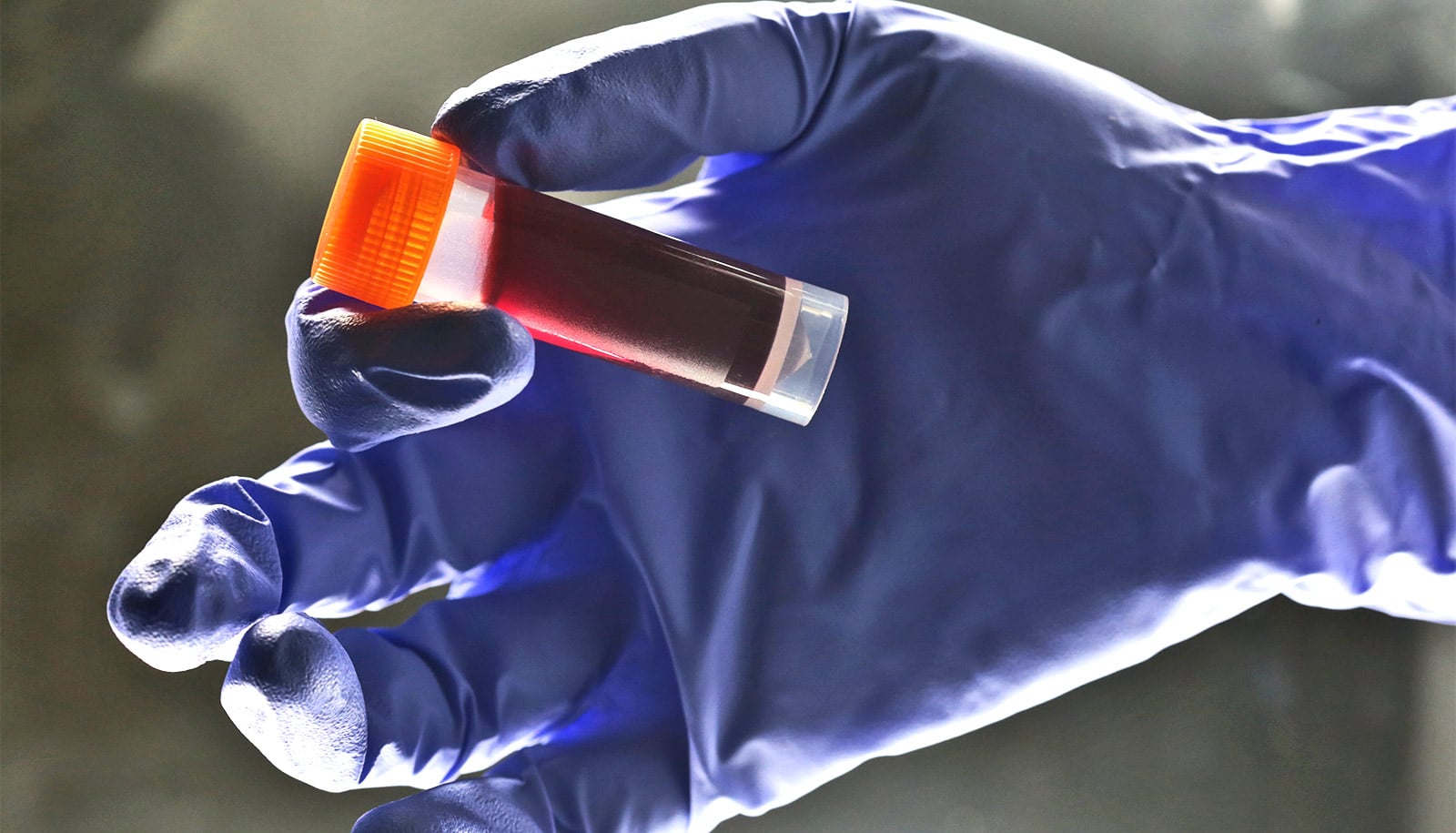

For the study, the researchers generated a cell “atlas” from bone marrow samples taken from six healthy people and 23 patients with CML prior to treatment. The atlas allowed them to see the different types of cells and their proportions in each sample. The researchers conducted RNA sequencing at the single-cell level and employed machine learning algorithms to determine which genes and molecular processes were turned on and off in each cell.

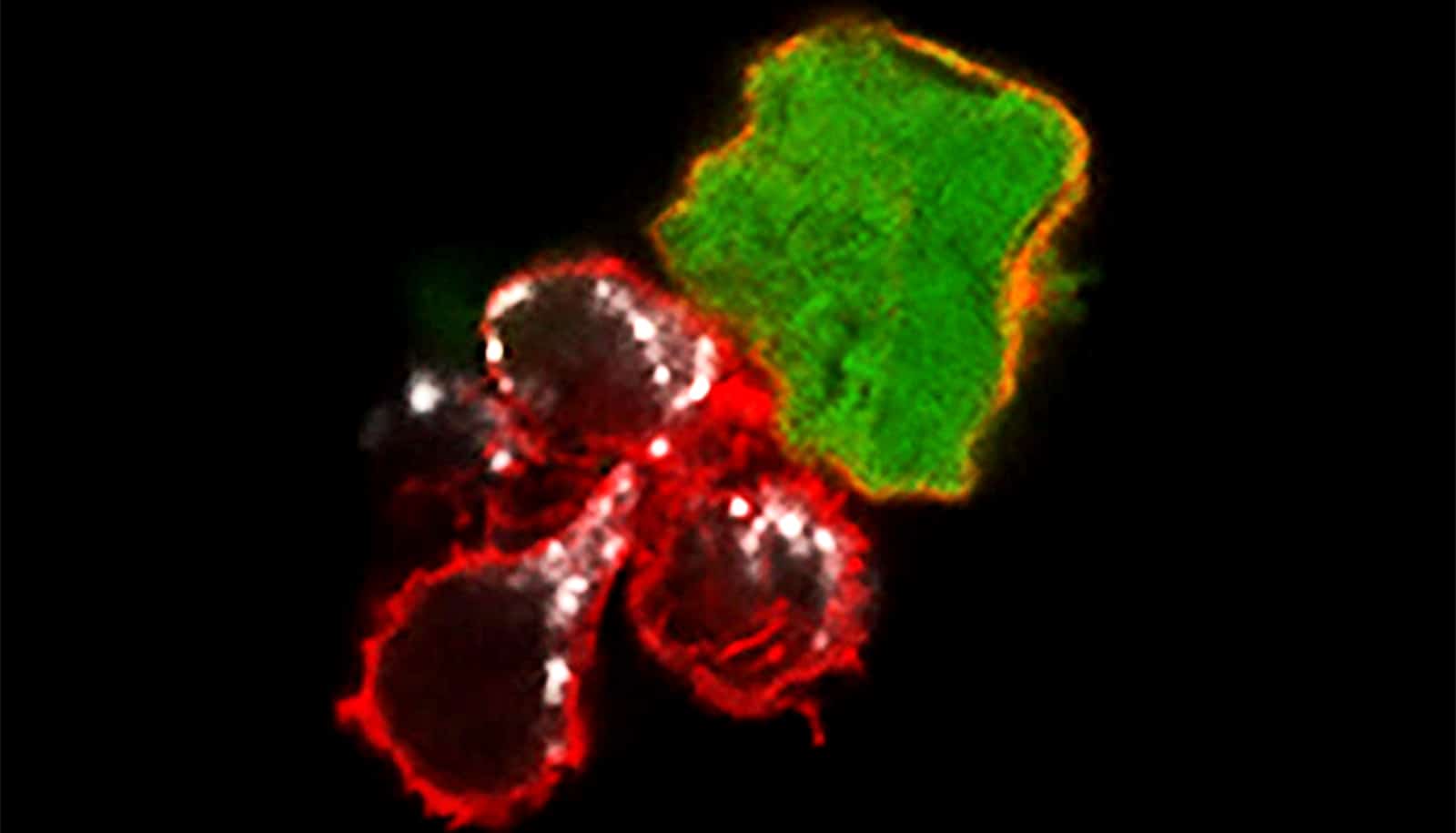

The work revealed eight statistically significant features in pre-treatment bone marrow cells that were either associated with sensitivity to tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment or extreme resistance to it.

Specifically, patients were more likely to respond well to leukemia treatment if their bone marrow samples showed a stronger tendency towards premature red blood cells and a specific type of tumor-destroying “natural killer cell.” As the proportions of these cells in the bone marrow shifted, patient response to treatment changed.

The research could lead to drug targets for preventing or delaying leukemia treatment resistance and blast crisis in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia.

“Treatment outcomes of chronic myeloid leukemia have improved tremendously over the years and many options are now available for our patients. Knowing which treatment works best for our patients will further enhance these outcomes and we are excited by the possibility of being able to do so,” says Charles Chuah, an associate professor from Duke-NUS’ CSCB Programme who is also senior consultant at the department of hematology at SGH and NCCS.

The team next plans to use the findings to develop a predictive test of treatment resistance that hospitals can routinely use with their patients.

Source: Duke-NUS