Astrocytes may be a key player in the brain’s ability to process external and internal information simultaneously, according to a new study.

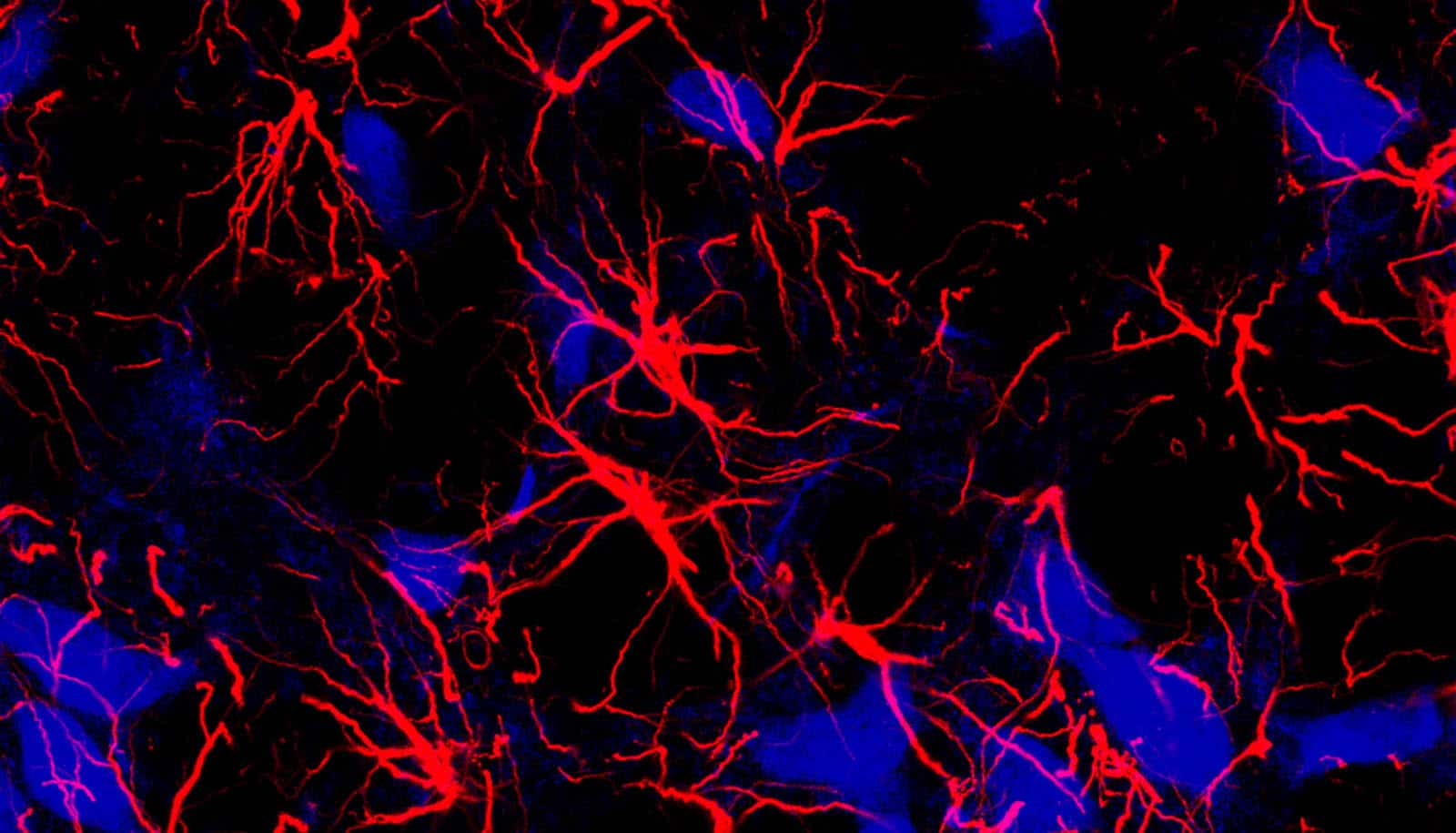

Long thought of as “brain glue,” the star-shaped cells called astrocytes are members of a family of cells found in the central nervous system called glial that help regulate blood flow and synaptic activity, keep neurons healthy, and play an important role in breathing.

Despite this growing appreciation for astrocytes, much remains unknown about the role these cells play in helping neurons and the brain process information.

“We believe astrocytes can add a new dimension to our understanding of how external and internal information is merged in the brain,” says Nathan Smith, associate professor of neuroscience at the Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience at the University of Rochester.

“More research on these cells is necessary to understand their role in the process that allows a person to have an appropriate behavioral response and also the ability to create a relevant memory to guide future behavior.”

The way our body integrates external with internal information is essential to survival. When something goes awry in these processes, behavioral or psychiatric symptoms may emerge.

Smith and coauthors point to evidence that astrocytes may play a key role in this process. Previous research has shown astrocytes sense the moment neurons send a message and can simultaneously sense sensory inputs. These external signals could come from various senses such as sight or smell.

Astrocytes respond to this influx of information by modifying their calcium Ca2+ signaling directed towards neurons, providing them with the most suitable information to react to the stimuli.

The authors hypothesize that this astrocytic Ca2+ signaling may be an underlying factor in how neurons communicate and what may happen when a signal is disrupted. But much is still unknown in how astrocytes and neuromodulators, the signals sent between neurons, work together.

“Astrocytes are an often-overlooked type of brain cell in systems neuroscience,” Smith says. “We believe dysfunctional astrocytic calcium signaling could be an underlying factor in disorders characterized by disrupted sensory processing, like Alzheimer’s and autism spectrum disorder.”

Smith has spent his career studying astrocytes. As a graduate student at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Smith was part of the team who discovered an expanded role for astrocytes. Apart from absorbing excess potassium, astrocytes themselves could cause potassium levels around the neuron to drop, halting neuronal signaling. This research showed, for the first time, that astrocytes did more than tend to neurons, they also could influence the actions of neurons.

“I think once we understand how astrocytes integrate external information from these different internal states, we can better understand certain neurological diseases. Understanding their role more fully will help propel the future possibility of targeting astrocytes in neurological disease,” Smith says.

The communication between neurons and astrocytes is far more complicated than previously thought. Evidence suggests that astrocytes can sense and react to change—a process that is important for behavioral shifts and memory formation.

The study authors believe discovering more about astrocytes will lead to a better understanding of cognitive function and lead to advances in treatment and care.

The study appears in Trends in Neuroscience.

Additional coauthors are from the University of Copenhagen.

The National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the European Union under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship, the ONO Rising Star Fellowship, the Lundbeck Foundation Experiment Grant, and the Novo Nordisk Foundation supported the work.

Source: University of Rochester