Anxiety, autism, schizophrenia, and Tourette syndrome each have their own distinguishing characteristics, but a new study asks if circadian rhythm disruption may bridge these and most other mental disorders.

In a new study in the journal Translational Psychiatry, scientists hypothesize that circadian rhythm disruption (CRD) is a psychopathology factor that a broad range of mental illnesses share. Research into its molecular foundation could be key to unlocking better therapies and treatments.

“Circadian rhythms play a fundamental role in all biological systems at all scales, from molecules to populations,” says senior author Pierre Baldi, professor of computer science at the University of California, Irvine. “Our analysis found that circadian rhythm disruption is a factor that broadly overlaps the entire spectrum of mental health disorders.”

Lead author Amal Alachkar, a neuroscientist and professor of teaching in the pharmaceutical sciences department, notes the challenges of testing the hypothesis at the molecular level but says thoroughly examining peer-reviewed literature on the most prevalent mental health disorders provided ample evidence of the connection.

“The telltale sign of circadian rhythm disruption—a problem with sleep—was present in each disorder,” Alachkar says. “While our focus was on widely known conditions including autism, ADHD, and bipolar disorder, we argue that the CRD psychopathology factor hypothesis can be generalized to other mental health issues, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, food addiction, and Parkinson’s disease.”

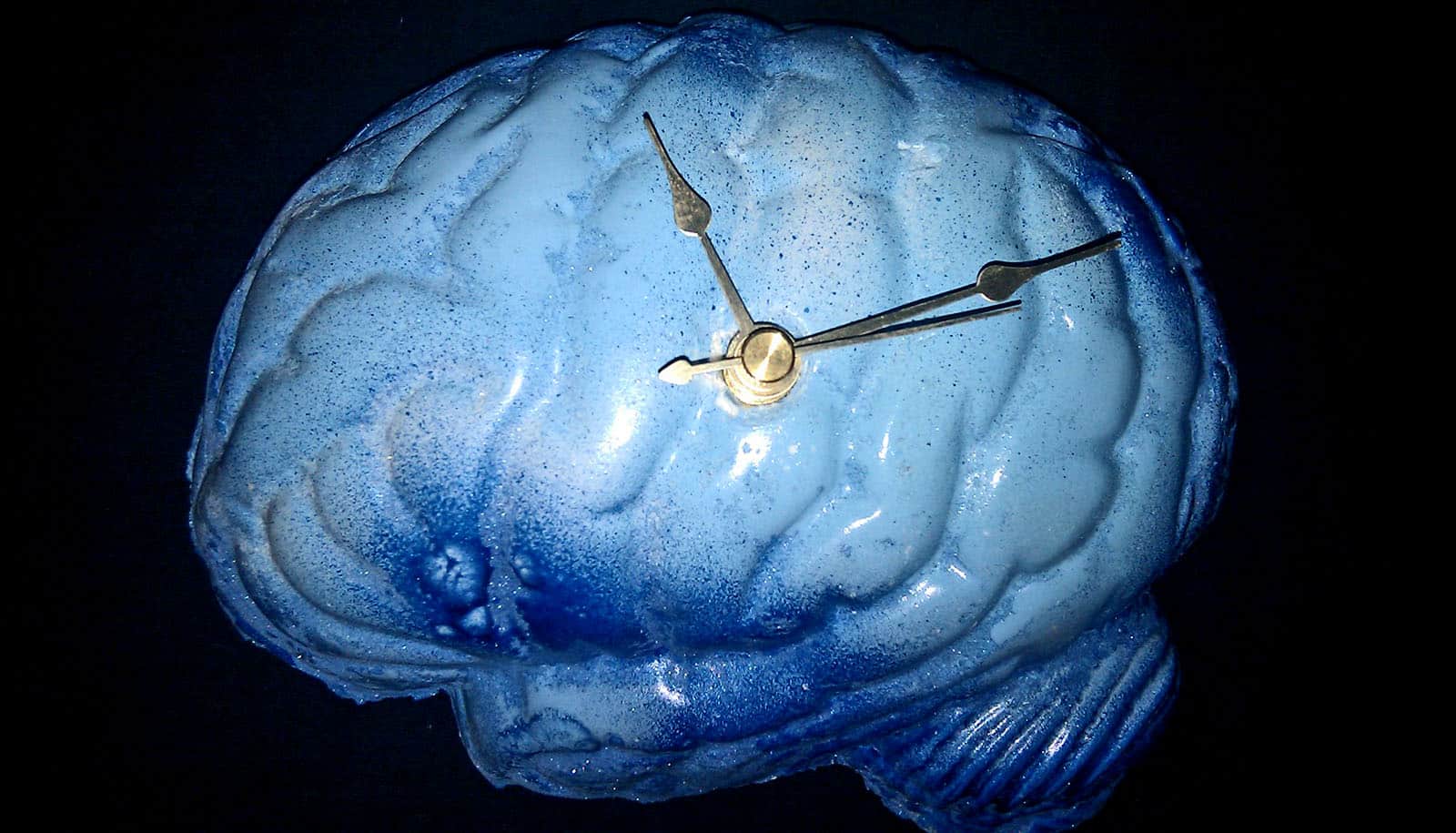

Circadian rhythms regulate our bodies’ physiological activity and biological processes during each solar day. Synchronized to a 24-hour light/dark cycle, circadian rhythms influence when we normally need to sleep and when we’re awake.

They also manage other functions such as hormone production and release, body temperature maintenance, and consolidation of memories. Effective, undisrupted operation of this natural timekeeping system is necessary for the survival of all living organisms, the paper’s authors say.

Circadian rhythms are intrinsically sensitive to light/dark cues, so they can be easily disrupted by light exposure at night, and the level of disruption appears to be sex-dependent and changes with age. One example is a hormonal response to CRD felt by pregnant women; both the mother and the fetus can experience clinical effects from CRD and chronic stress.

“An interesting issue that we explored is the interplay of circadian rhythms and mental disorders with sex,” says Baldi, director of the Institute for Genomics and Bioinformatics. “For instance, Tourette syndrome is present primarily in males, and Alzheimer’s disease is more common in females by a ratio of roughly two-thirds to one-third.”

Age also is an important factor, according to scientists, as CRD can affect neurodevelopment in early life in addition to leading to the onset of aging-related mental disorders among the elderly.

An important unresolved issue centers on the causal relationship between CRD and mental health disorders, Baldi says. Is CRD a key player in the origin and onset of these maladies or a self-reinforcing symptom in the progression of disease?

To answer this and other questions, the researchers suggest an examination of CRD at the molecular level using transcriptomic (gene expression) and metabolomic technologies in mouse models.

“This will be a high-throughput process with researchers acquiring samples from healthy and diseased subjects every few hours along the circadian cycle,” Baldi says. “This approach can be applied with limitations in humans, since only serum samples can really be used, but it could be applied on a large scale in animal models, particularly mice, by sampling tissues from different brain areas and different organs, in addition to serum. These are extensive, painstaking experiments that could benefit from having a consortium of laboratories.”

He adds that if the experiments occur in a systematic way with respect to age, sex, and brain areas to investigate circadian molecular rhythmicity before and during disease progression, it would help the mental health research community identify potential biomarkers, causal relationships, and novel therapeutic targets and avenues.

Additional coauthors are from the University of California, Los Angeles; and UC Irvine. The National Institutes of Health provided financial support.

Source: UC Irvine