Certain deep-sea fish seem to use volcanic heat from hydrothermal vents to accelerate the development of their embryos. This behavior hasn’t been seen before in marine animals.

The fish, deep-sea skates—cartilaginous fish related to rays and sharks—have some of the longest egg incubation times, estimated to last more than four years.

“Hydrothermal vents are extreme environments, and most animals that live there are highly evolved to live in this environment,” says Charles Fisher, professor of biology at Penn State and an author of the paper in Scientific Reports. “This study is one of the few that demonstrates a direct link between the vent environment and animals that live most of their life elsewhere.”

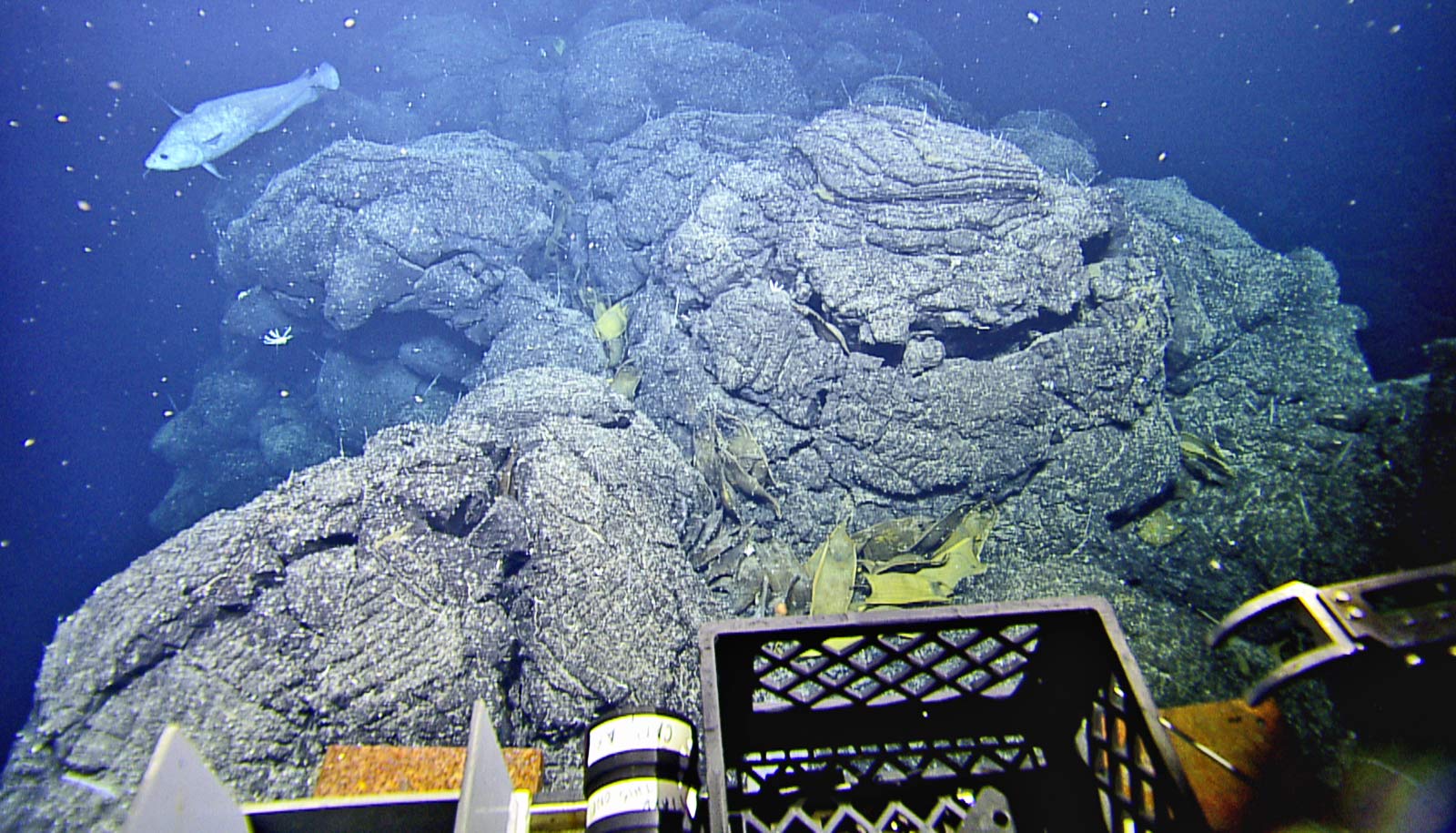

Among the least explored and unique ecosystems, deep-sea hydrothermal fields are regions on the sea floor where hot water emerges after being heated in the ocean crust. In their study, a team of researchers used a remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV) to survey in and around an active hydrothermal field located in the Galápagos archipelago, 28 miles north of Darwin Island.

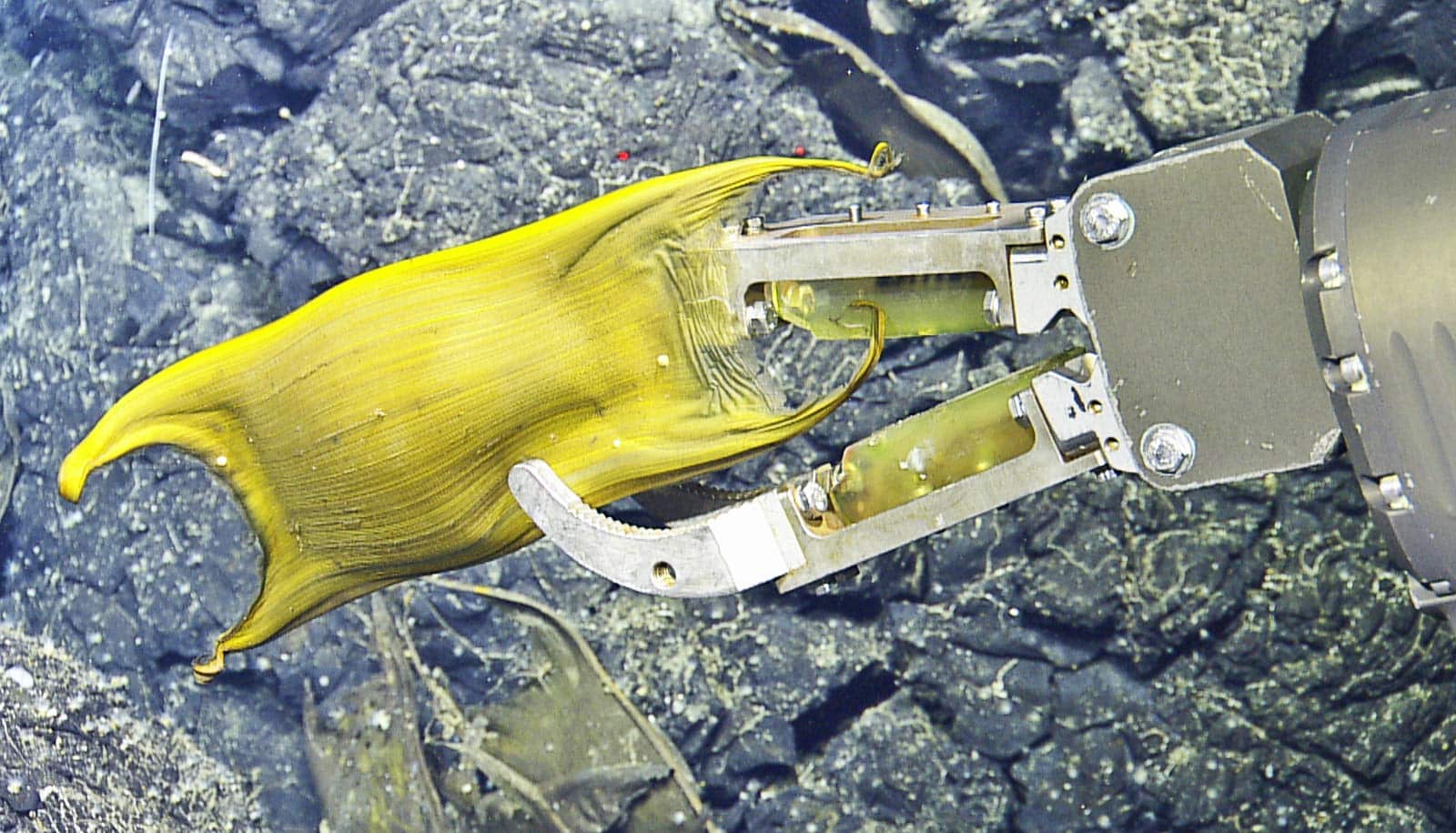

“When we panned the camera down, we found something we did not expect: These giant egg cases, also known as mermaid purses.”

“The first place the ROV landed on the sea floor was on a ridge, in the plume of a nearby hydrothermal vent that we had specifically come to investigate—a black smoker,” says Fisher.

“When we panned the camera down, we found something we did not expect: These giant egg cases, also known as mermaid purses. And we found several layers of them, indicating that whatever was laying these eggs had been coming back to this spot for many years to lay them. As the dive progressed, we saw more and more of these egg cases and realized that this was not the result of a single animal, but rather a behavior shared by many individuals.”

The researchers found 157 egg cases in the area and collected four with the ROV’s robotic arm. DNA analysis revealed that the egg cases belonged to the skate species Bathyraja spinosissima, one of the deepest-living species of skates that is not typically thought to occur near the vents.

The majority—58 percent—of the observed egg cases were found within about 65 feet of the chimney-like black smokers, the hottest kind of hydrothermal vents, and over 89 percent had been laid in places where the water was hotter than average. The researchers believe that the warmer temperatures in the area could reduce the typically years-long incubation time of the eggs.

“The deep sea is full of surprises.”

While several species of reptiles and birds lay their eggs in locations that optimize soil temperatures, only two other groups of animals are known to use volcanically heated soils: the modern-day Polynesian megapode—a rare bird native to Tonga—and a group of nest-building neosauropod dinosaurs from the Cretaceous Period.

Because of their long lifespan and slow rate of development, deep-water skates may be particularly sensitive to threats to their environment, including fisheries expanding into deeper waters and sea-floor mining. Understanding the development and habitat of the skates is vital for developing effective conservation strategies for this poorly understood species.

Can shark eggs clarify how human necks develop?

“The deep sea is full of surprises,” says Fisher. “I’ve made hundreds of dives, both in person and virtually, to deep sea hydrothermal vents and have never seen anything like this.”

In addition to Fisher, the research team includes investigators from the Charles Darwin Research Station in Ecuador and the National Geographic Society; Harvard University and the University of Rhode Island; the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, California Academy of Sciences, and the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity; Nova Southeastern University; and the University of Southampton, Waterfront Campus, and the National Oceanography Centre, both in the United Kingdom.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Helmsley Charitable Trust, and the Save Our Seas Foundation funded the work.

Source: Gail McCormick for Penn State