Researchers have discovered a simple, practical way to use light and optics to steer killer immune cells toward tumors. It’s a step in the complicated science behind harnessing the immune system to fight cancer.

In Nature Communications, lead author Minsoo Kim, professor of microbiology and immunology and a Wilmot Cancer Institute investigator at the University of Rochester, describes his method as similar to “sending light on a spy mission to track down cancer cells.”

Immunotherapy is different from radiation or chemotherapy. Instead of directly killing cancer cells, immunotherapy tells the immune system to act in certain ways by stimulating T cells to attack the disease. Several different types of immunotherapy exist or are in development, including pills called “checkpoint inhibitors” and CAR T-cell therapy that involves removing a patient’s own immune cells and altering them genetically to seek and destroy cancer cells.

The problem, however, is that immunotherapy can cause the immune system to over- or under-react, Kim says. In addition, cancer cells are evasive and can hide from killer T-cells. Aggressive tumors also suppress the immune system in the areas surrounding the malignancy (called the microenvironment), keeping T cells out.

If the immune system under-reacts, currently the only way to modify it is to pump more T cells into the body. But that often unleashes a storm of toxicities that can shut down a patient’s organs. Kim’s laboratory focused on how to overcome the immune-suppressive environment that cancer creates, in two separate projects:

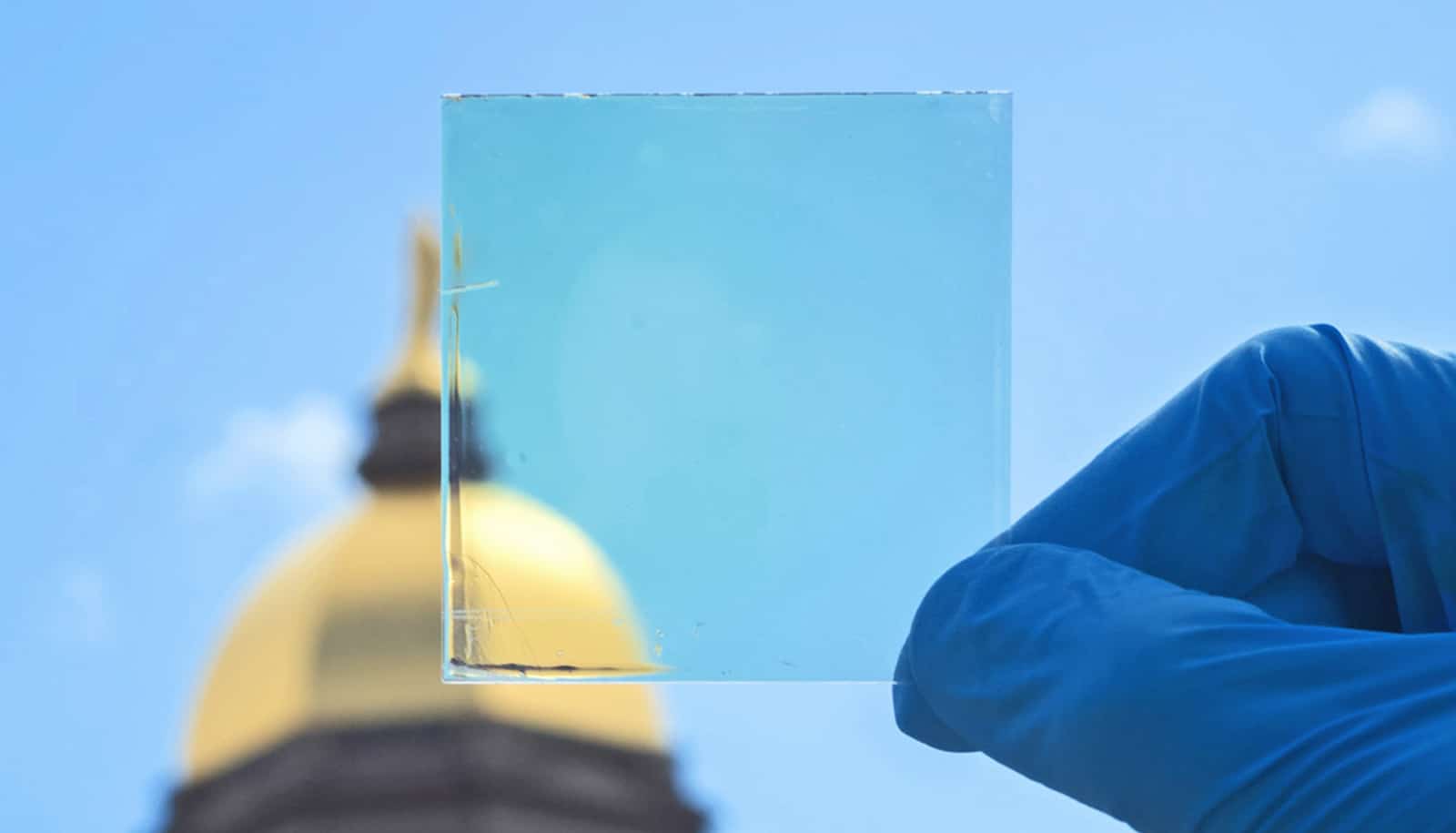

- A biological study to understand and develop light-sensitive molecules that could efficiently guide T cells toward tumors. They discovered that a molecule called channelrhodopsin (CatCh), which is active in algae and is light sensitive, could be introduced to the immune system via a virus and activated to control the T- cell response to cancer.

- An engineering study to invent an LED chip to test in mice. It could eventually be an implant for humans.

Kim’s lab, as well as scientists in optics and photonics, evaluated their methods in mice with melanoma on their ears. The animals wore a tiny battery pack that sent a wireless signal to the LED chip—allowing researchers to remotely shine light on the tumor and surrounding areas, giving T cells a boost for their cancer-killing function.

The optical control was sufficient to allow the immune system to nearly wipe out the melanoma with no toxic side effects, the study reports.

Future studies, Kim says, would determine whether the wireless LED signal can deliver light to a tumor deep within the body instead of on the surface area, and still have the ability to stimulate T cells to attack.

Immunotherapy for cancer is a hot area of research, as scientists try to improve the success rate of this treatment. Currently less than 40 percent of patients who receive immunotherapy get good results, although those who do respond are often dramatically better.

Shedding mutations may let cancer evade immunotherapy

Kim emphasizes that his discovery is meant to be combined with immunotherapy to make it safer, more effective, and traceable. With improvements, Kim says, the optical method might allow doctors to see, in real time, if the cancer therapy is reaching its target. Currently when a patient receives immunotherapy he or she must wait for several weeks and then undergo imaging scans to find out if the treatment worked.

“The beauty of our approach is that it’s highly flexible, non-toxic, and focused on activating T cells to do their jobs,” Kim says.

UR Ventures, the university’s technology transfer office, has filed for patent protection on the invention.

The National Institutes of Health funded the research.

Source: University of Rochester